|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

|

The Hissem-Montague Family  |

This branch of the family is famous for a prominent line of physicians, including the inventor of the heart-lung bypass machine, and an Army Major General of the Union Army during the Civil War and his Confederate brothers.

(21) Mary Heysham-Gibbon (1761)

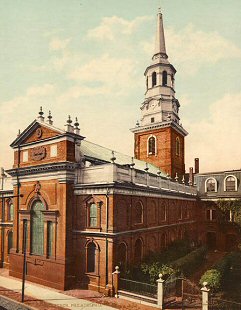

(21) Mary Heysham-Gibbon (1761)Mary is the matriarch of this line. She was the oldest daughter of Captain William Heysham of Philadelphia. She was born on 29 December 1761 and christened on 03 January 1762 at Christ Church and Saint Peters, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Saint Peters was a subsidiary to Christ Church, built when the congregation became too large for the older facility. I suspect Mary's christening was taken from a joint record of the two churches, so she was christened in one church or the other, not both. Looking at her father's record and her marriage, I'll assume she was christened at the larger, and more prestigious, Christ Church, pictured to the right.

Like her younger sister, Ann, she was the daughter of a prosperous ship-captain/merchant and, as such, lived a relatively privileged life on Arch street, in Philadelphia, pictured to the left. The Captain's family lived on the left (north) side of the street, several houses up from the intersection, which is 4th Street. The home of Betsy Ross was amongst the same row of houses. The church in the background is the Second Presbyterian. Across the street, on the south side of Arch street, a low brick wall can be seen which surronded the Quaker Meeting House and burial ground.

Like her younger sister, Ann, she was the daughter of a prosperous ship-captain/merchant and, as such, lived a relatively privileged life on Arch street, in Philadelphia, pictured to the left. The Captain's family lived on the left (north) side of the street, several houses up from the intersection, which is 4th Street. The home of Betsy Ross was amongst the same row of houses. The church in the background is the Second Presbyterian. Across the street, on the south side of Arch street, a low brick wall can be seen which surronded the Quaker Meeting House and burial ground.

Mary would have received a basic education in reading, writing, some arthimetic and morals, but it was from her mother that she would have gained her real education in how to run a household, raise an upstanding family, and be a suitable consort of an up-and-coming young man.

Mary was 13 years old when the Revolution began at Lexington & Concord in 1775, and 15 when the army of General Howe occuppied Philadelphia. This was a dangerous time for her family because they were known to oppose the King. Mary's father was a radical in the forefront of the patriot cause and had angered many of his Loyalist neighbors. He was arrested soon after the occupation, though how long he was held I don't know. Mary's brother, William Jr., was at sea, an officer onboard an American privateer, the REVENGE, that had gained an evil reputation in England. Her other brother, Robert, was in the militia and had fought against the British at Trenton and Brandywine. I suspect Mary, her sister, and her mother also aided the rebel cause in the same manner women over the ages have done, in making bandages, knitting & sewing garments and blankets for the soldiers, etc.

It's possible given their background that the family either fled the city or that their home was commandeered and they were forced to live elsewhere. Their house was in one of the better neighborhoods and centrally located, and so would have been a prime property for housing British officers. If so it undoubtedly suffered as a result. While the occupation was not a severe one, the troops took as good a care of property that was not their own as you might expect. When the British departed, many portable goods left with them. In an assessment of the damages sustained during the occupation, William Heysham claimed a loss of 286 [pounds] 3 [shillings].

After the British left Philadelphia in June 1778 Mary's father, William Sr., renewed his activities in various radical patriot organizations. Her brother Robert mustered with Captain George Esterly's company of militia, although Philadelphia was never directly threatened again. William Jr. was taken by a British warship while piloting the prize BETSEY back to an American port and spent the next 2 years in Portsmouth prison.

Meanwhile, the war in America took another turn with the British embarked on a campaign in the South. This would end with the British army under General Cornwallis trapped at Yorktown, Virginia and forced to surrender to a combined American and French force.

In 1783 the war was over and the United States was now a free nation. Mary's father continued to take an interest in government and politics. In 1788 a parade was held in Philadelphia celebrating the establishment of the Constitution. Brother Robert led a corps of infantry and father William rode in a float representing the Sea Captains Club.

Nothing is known of Mary until 1787 when she was confirmed.

""1787. Names of Persons confirmed in St Peters Church, in the City of Philadelphia, on the 10th Day of November, 1787

. . .

Mary Heysham" - from "Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Church and Town Records, 1708-1985"

Mary Heysham was a witness and heir, along with her mother and sister, to the will of Susannah Cumming of Philadelphia. The will was signed 17 November 1789 and proved on 26 April 1791. Mary's father and brother, Robert, were executors.

"Cumming, Susannah. (Late of City of Phil'a.) Mooreland, Co of Philad'a. Widow. Signed Nov. 17. 1789. Son- Joseph. Nieces- Margaret Craft and her Daughter Maria. Nephew- James Craft. Friends- Mrs. Mary Heysham and her Daughters Mary and Ann, Katharine, Mary, Phibe, and Rachel Comley, James Mounteer. James (Son of Joshua Comley). Exec. Joseph Cumming, Robert Heysham, William Heysham Senr. Witnesses- Joshua Comly, Ann Heysham. Prov'd. Ap. 26. 1791."Mooreland, or Moreland, was a township in northeastern Philadelphia.

The census of 1790 shows three women living in William Heysham's house on Arch street. These were most likely William's wife and two daughters, Mary and Ann.

Mary Heysham married Dr. John Hannum Gibbons, a Quaker, in 1794 in Philadelphia.

"In 1794, he and Mary Heysham were married; he was thirty-five at the time, she thirty-three. Mary's father had emigrated in 1721 [sic] from Lancaster, England, to New York where he had met and married her mother, also named Mary. They moved to Philadelphia shortly after the daughter was born. Dr. Gibbons and his wife had only a short while together for he died the following year, on October 4; their son, John Heysham, was only eight months old. Dr. Gibbons was interred in the burial grounds of Christ Church at Fifth and Archer Streets, just opposite the grave of Benjamin Franklin." - from "A Dream of the Heart" by Harris B. ShumackerJohn Gibbon's family had come to America from Wiltshire, England in 1684. He was a physician and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania. He received "a part of his education in Edinburg, Scotland" - from "Genealogy of the Hannum Family." His practice was in Philadelphia and the couple settled on Arch street, perhaps in her father's house. It is interesting to note that Mary's sister, Ann, also married a Doctor, Francis Bowes Sayre, in 1792. Did the doctors meet the two sisters through their own mutual acqauintance, or vice versa [interesting, too, that the younger sister married first]? Also of interest was that the Gibbons family were Quakers. Was John Hannum Gibbons still a Quaker at the time of his marriage and, if not, when did he change?

John had graduated from the University of Edinburgh of Medicine in 1786. "In 1789 and for some years afterwards he lectured on the "Theory and Practice of Medicine." - from "History of medicine in the United States: With a Supplemental Chapter on the Discovery of..." by Francis Randolph Packard.

Interestingly, "Dr. John Hannum Gibbons, Philadelphia physician" was mentioned by John Adams in a Letter to Thomas Jefferson, in London, on 30 November 1786 - from "The Adams-Jefferson Letters: the complete correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and Abigail and John Adams," edited by Lester J. Cappon, pg 156. It was in this letter that Jefferson first learned of "Shay's Rebellion" in western Massachusetts. In his reply he famously said "I like a little rebellion now and then. It is like a storm in the atmosphere." I haven't looked up this book yet.

| The Gibbons Family

The family of John Hannum Gibbons. |

Dr. Gibbon and his new wife settled down in Arch Street, perhaps living with Mary's father, William Heysham. - from "History of medicine in the United States: With a Supplemental Chapter on the Discovery of..." by Francis Randolph Packard.

At the end of the summer of 1793 the Yellow Fever had returned to Philadelphia. People developed violent fevers, yellow skin, and black vomit (from intestinal hemorrhages), and often died within a few days. In response to a request by the Mayor, 16 of the 26 Fellows of the College of Physicians met to discuss what should be done. Among the Fellows was John H. Gibbons - From "Bring out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793" by J. H. Powell, 1993. Note that Dr. Adam Kuhn, another Fellow, who had a run-in with Mary's father, William Heysham, was greatly vilified for leaving town at this time to live in Bethlehem. He left many patients behind that other doctors had to treat. Gibbons himself became ill from the fever in September, though he apparently recovered. Unlike Dr. Frances Sayre, his brother-in-law, he was not a protege of Benjamin Rush, but more closely his equal. When the epidemic faded in November, one-tenth of the city's residents had died and over 17,000 others had fled the city.

| The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

The College was founded on 2 January 1787 by twenty-four prominent Philadelphians, including John Redman (1722-1808), elected first president of the College, John Morgan (1735-1789), founder of America's first medical school, and Benjamin Rush (1745-1813), a signer of the Declaration of Independence and vigorous advocate of many humanitarian and social causes. The College, according to its constitution, was founded "to advance the Science of Medicine, and thereby lessen Human Misery, by investigating the diseases and remedies which are peculiar to our country" and to promote "order and uniformity in the practice of Physick." The College's members immediately became involved in public health issues. In 1787 they published a temperance memorial. Then, "When Yellow Fever struck the city in 1793, the vexed question of whether the disease was local in origin or had been imported from the West Indies divided physicians not only in Philadelphia but also elsewhere. At the same time, Benjamin Rush, an enthusiastic purger and bleeder, had introduced his famous ten-and-ten treatment-ten ounces of blood and ten of calomel (mercury)-a therapy which led to considerable "contrariety of opinion" between Rush and his fellow College members. In response to queries from the Governor of Philadelphia, the College supported the importation theory of Yellow Fever, an opinion that Rush opposed and that, together with arguments over his heroic treament, led to his resignation from the College." - from a review of "The College of Physicians of Philadelphia: a bicentennial history" by Whitfield J. Bell Jr., 1988.In 1793 the College had 26 Fellows, all doctors. A special meeting of the members was called to answer Governor Mifflin and Mayor Mathew Clarkson's questions about the fever then raging in the city. The Fellows attending were William Shippen, the College's Vice President, Samuel Powell Griffitts, its Secretary, Benjamin Say, the Treasurer, Adam Kuhn, Thomas Parke, Caspar Wistar, Benjamin Duffield, Samuel Duffield, John H. Gibbons, Andrew Ross, John Carson, William McIlvaine, Nathan Dorsey, Benjamin Rush, William Currie, and James Hutchinson, the Port Physician. Non-attendees included John Redman, the College's President, Michael Leib, Peter Glentworth, Robert Harris, Waters, and John Foulke. |

John was an Edinburgh-trained physician and this may have been his introduction into the higher levels of medical society in Philadelphia and for admission to the College of Physicians.

| The Edinburgh Influence

Edinburgh was at this time the most famous place for medical education in Europe, certainly for English speaking students. It was here that the foundation was laid for what proved to be the beginning of medical teaching at Philadelphia. John Morgan met there an old fellow student at Dr. Finley's Academy, William Shippen Jr., son of a Trustee of the Philadelphia College. Morgan and Shippen would later found the medical school at the University of Philadelphia. Adam Kuhn and Benjamin Rush, both Edinburgh graduates, were added as lecturers in the school's first year. Each man maintained his own private practice as well. Note, above the entrance to the medical school is carved the thistle of Scotland, a tribute to the influence of Scotland on the school and medicine. |

John's brother-in-law, Francis Bowes Sayre, was an associate of Benjamin Rush, one of America's most famous doctors. Rush exchanged medical data with numerous doctors, including a Dr. John Gibbons of Delaware. John H. Gibbons was from Delaware county. Could this be the same man? Could Ann and Mary Heysham's husbands have met through their mutual acquaintance with Rush?

John Hannum Gibbons died soon after he married, on 4 October 1795, predeceasing his own father by 4 years. He was only 36 years old. This would have been just 8 months after the birth of his son, John Heysham Gibbon. There is no indication of how, or from what, he died, but as a Doctor he frequently came in contact with infectious diseases. Note that Yellow Fever struck Philadlephia in 1793, 1794, 1797, 1798, 1802, 1803, 1805, 1819, 1820, and 1853.

"All persons indebted to the Estate of Doctor John H. Gibbons, late of Philadelphia, deceased, are requested to make payment; and those who have any demands against said Estate, are desired to bring inn their accounts duly attested, for settlement, toAn attorney in fact is a person who is authorized to perform business-related transactions on behalf of the principal. Authorization is provided through a power of attorney.

Robert Heysham

Attorney in fact for Mary Gibbons, administratrix to the said deceased's Estate.

Arch-street, No. 107; Nov. 4." - from the "Gazette of the United States" of 26 November 1795

Mary Heysham was "Rvcd on Trial" as a member of the Union Methodist Episcopal Church on 2 October 1810, and into full membership on 10 April 1811. Why didn't she use her Gibbon name? The Methodist Episcopal Church, sometimes referred to as the M.E. Church, was a development of the first expression of Methodism in the United States. The current church building was constructed in 1888 and is today the Jones Tabernacle AME Church.

Mary Heysham Gibbons died 29 years later, on 29 January 1824, while still living in Philadelphia, and was buried alongside her husband at the Christ Church Burying Ground. She and John had only one child,

(22) Dr. John Heysham Gibbon (1795)

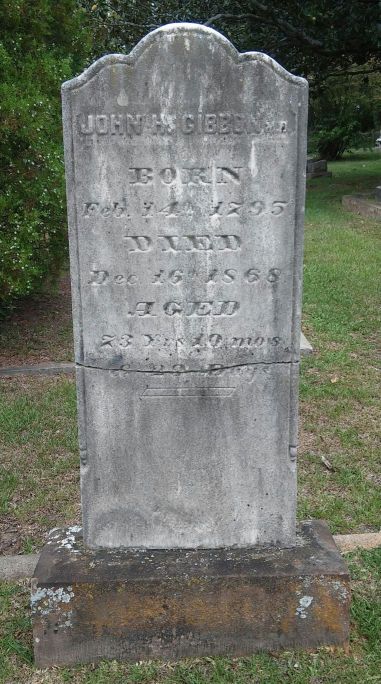

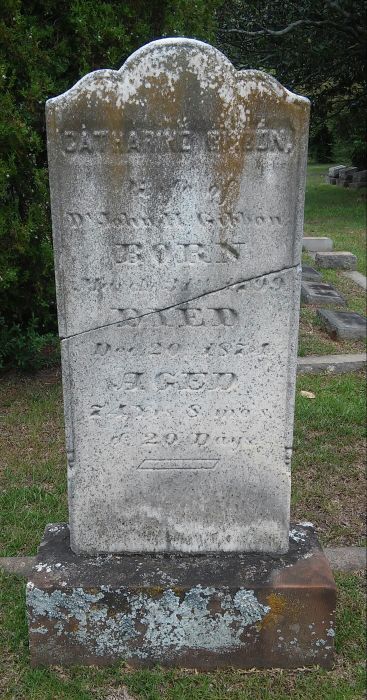

He was born on 14 February 1795 [his tombstone shows 1796] in Philadelphia [or possibly Westtown, Chester county, next door to Philadelphia]. His father died 8 months later, perhaps of the Yellow Fever which was recurrent through the 1790's. Did John's widowed mother receive support from the Gibbons, Hannum or Heysham families? John was named in his Grandfather Joseph Gibbons' will of 18 August 1796. It provided for his grandson, referred to as John Haysham [sic] Gibbons of Philadelphia, "when of age." His uncles James M. Gibbons and Joseph Gibbons were executors of the will and probably helped fund young John's education. William Heysham, his maternal grandfather, was also alive at this time and capable of providing support.

He studied medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, perhaps in memory of his father and at the urging of his mother, but he never practiced. He probably attended the school from about 1815 to 1820, or thereabouts. Note that in 1816, at the age of 21, he would have received the bequest from his grandfather's will.

John married Catherine Lardner [sometimes referred to as Katherine] on 4 November 1819. She was born on 31 March 1799 [or 1800] in Philadelphia, the daughter of William Lardner, of "Lynfield," near Holmseburg in Philadelphia county, and Ann Shepard [Shepherd], of Newborn, North Carolina. This was an excellent marriage. William was the son of Lynford Lardner, the elder, who had been an attorney for the Penn family and a member of the Pennsylvania Provincial Council.

John and Catherine had ten children, Lardner, Robert, Mary, John Hannum, Catherine, Anna, Virginia, Nicholas Biddle, Margaret and Frances, who died young.

| The Lardner Family

The family of Catherine Lardner's father. |

| The Shepard Family

The family of Catherine Lardner's mother. Note that Catherine's son, Lardner Gibbon, would marry Alice Shepard, his second cousin, below. |

In the 1830 census for Lower Dublin township, Philadelphia county, Pennsylvania as John H. Gibbon. The village of Holmesburg, where his children were born, was situated in Lower Dublin Township. At the time he had 1 boy under 5, two boys who were 5-10, and one man 30 to 40 years old. Women in the house included 1 girl under 5, 1 who was 5 to 10, and 1 woman 30 to 40 years old.

In 1832 John H. Gibbon, Dem, appears on a list in both the 'Star and Republican Banner' and the 'Gettysburg Compiler,' two newspapers of the day, as a newly elected Representative to the Pennsylvania State House of Representatives from Philadelphia county. Lynford Lardner, the younger, his wife's cousin, was also elected. This would have been a two-year term. The House was made up of 61 Democrats, 33 Anti-Masons, 5 National Republicans and 1 Undetermined. Pennsylvania was primarily a Democratic party state, having turned against what many saw as the aristocratic leanings of the Federalists. Both governors from 1823 to 1834 were Democrats. Politics changed in 1834, however, when a Whig party candidate took the governorhsip. Note that the state government was located in Harrisburg.

Also in 1832, and perhaps related to his election that year, an act was passed to incorporate the Philadelphia and Trenton railroad company. Dr. J.H. Gibbon, of Philadelphia was amongst a long list of men "appointed commissioners, to construct a railroad of one or more tracts, from the district of Kensington, through the borough of Frankford, intersecting the Delaware division of the Pa. canal, in the borough of Bristol, to the Trenton Delaware bridge in the borough of Morrisville. 23 Feb 1832." - from "The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania," Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1911, Laws Passed Session 1831-1832. I suspect this meant that the Doctor was one of the lines' backers and early shareholders.

| Philadelphia and Trenton Railroad

The P&T was chartered on 23 February 1832 by the Pennsylvania State Legislature. It was organized on 9 June 1832 with a captilization of $600,000. A stock offering was made that was easily sold out and construction began immediately. "When organizers of the new Philadelphia and Trenton Railroad decided, with the approval of the distant state legislature, to run their tracks down the center of Front Street to their depot at Third and Willow, East and West Kensingtonians buried their differences to preserve their communities from cinder-throwing machines. They united in a drawn-out series of disturbances and altercations known as the Railroad Riots. After workmen had finished laying track and ties during the day, local residents would rip out the work overnight, burning the ties to melt and warp the rails. After months of turmoil, the railroad directors decided to concede defeat and the Kensington Depot was finally constructed at Front and Berks Streets." From The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, "Old Kensington," by Rich Remer.

This was one of several very early rail lines operating out of Philadelphia. The earliest, the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown railroad, began operation in June 1832 with the cars drawn by horses. In November of that year the innovation of steam locomotives was introduced. It had a speed of about 28 miles per hour. A second line, the Delaware and Schuykill railroad, continued to be horse-drawn in 1834. The P&T used a locomotive from the outset, most likely a Baldwin model, made in Philadelphia, like the one pictured above. The chartering of railroad lines by the state assembly were surronded by intimations of corruption. |

I wonder how the Doctor did in the stock sale? It was about this time that John began looking for a midshipman's berth on a Navy ship for his eldest son, Lardner. John's position in the Assembly probably helped in that endeavour. Unless re-elected, John would have been out of office by the end of 1834 and looking for something to do.

In 1835 John appears to have accompanied Charles Biddle in a survey of the Panama Isthmus for a possible railroad. I wonder whether Biddle took Gibbon along for his knowledge of mineralogy (assuming he had any), of railroads, of the financing of railroads, or simply as a companion. The following indicates that he was an interpreter, but did he really speak Spanish or was this meant more broadly as an "interpreter of the sights?"

"Dr. John Heysham Gibbon was an intelligent and likable physician who enjoyed a good life in Philadelphia. In 1836, he served as an interpreter to a member of an important family on a trip to Panama." - from "A Dream of the Heart: The Life of John H. Gibbon Jr." by Harris B. ShumackerCharles Biddle was the son of Captain Charles Biddle and Hannah Shepard, and the brother of Nicholas Biddle, the head of the Bank of the United States. Hannah Shepard's sister was John H. Gibbon's mother-in-law. From "Isthmus of Panama: History of the Panama Railroad" by F.N. [Fessenden Nott] Otis, M.D, New York, 1867:

"Pursuant to a resolution offered by the Hon. Henry Clay, of Kentucky, in the Senate of the United States, in the year 1835, the President, General Andrew Jackson, appointed Mr. Charles Biddle, formerly of Philadelphia, then of Tennessee, as a commissioner to visit the different routes on the Continent of America best adapted for inter-oceanic communication, and to report thereon, with reference to their value to the commercial interests of the United States.See also "A Philadelphian and the Canal: The Charles Biddle Mission to Panama."

Mr. Biddle, accompanied by Dr. Gibbon, of Philadelphia, sailed from that port for St. Jago de Cuba, to gain preliminary information regarded to be important." See Isthmus of Panama for the complete book.

The Panama Railroad The Panama Railroad

In 1835 President Jackson commissioned Charles A. Biddle, an Army Colonel, to go to Nicaragua and the Isthmus of Panama, survey the ground, and report on the different routes which had been proposed for interoceanic communication. Biddle, being greatly impressed with what he saw of the Panama route, did not carry out the whole of his instructions, never visiting Nicaragua, but instead proceeded to Bogota, where he succeeded in securing a private franchise for a trans-Isthmian railroad. This action put his mission and his reputation under a cloud. He returned to the United State in 1837 with this franchise, but died before he was able to prepare a report.

|

The Panamanian travelors returned to the United States late in 1836, but Charles Biddle died soon thereafter, on 31 December 1836. An official report of the expedition was never made. Note that John's eldest son, Lardner, mimiced his father's adventure, making his own expedition to South America in 1851.

By this time John may have been looking for a government sinecure. On 27 February 1837 the President, Andrew Jackson, nominated J. H. Gibbon to be assayer of the branch mint at Charlotte, North Carolina. On 2 March the Congress consented. In 1838 Gibbon accepted the appointment and moved his family there.

Was John a trained mineralogist or was his appointment purely political? While he may have been an amateur "rock hound," and could have practiced this avocation in Panama, I have to think he was chosen more because of his family and political connections.

Men hired to make coins at the Charlotte facilty attended special training at the Mint in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and John probably did too. When the Charlotte Mint opened, the superintendent's salary was $2,000 per year. The chief coiner, John R. Bolton, earned $1,500 per year. The assayer, J. H. Gibbon, earned $1,000 per year.

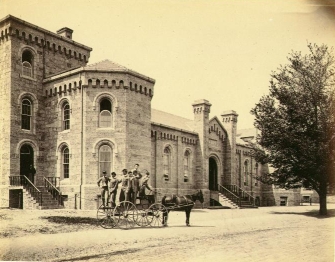

| The Charlotte Mint

In 1788 young Conrad Reed found a shiny 17-pound rock in Cabarrus County, North Carolina. His family used the rock for years as an interesting doorstop. That is, until they discovered it was gold. This gold find triggered America's first gold rush in the early days of the republic while George Washington was still President. During its peak years gold mining employment was second only to farming in the South. Over a million dollars a year was mined in gold in the early 1800s. In fact, North Carolina led the nation in gold production until 1848 when it was eclipsed by the California Gold Rush.

On the night of 27 July 1844, the Charlotte Mint was nearly destroyed by fire, which occurred in the coining room and nearly consumed the entire building. The machinery was seriously injured, but the records, being stored in the vault, were not injured. Mr. Caldwell, the superintendent, reported that evidently the fire was the work of a thief, as his living apartments had been entered and articles stolen. The present building, pictured above, was authorized by Act of 3 March 1845 and was completed at a cost of $31,572.97, and occupied in 1846, and used for coinage purposes until May 20, 1861, when North Carolina entered the Confederacy and operations were suspended. After Abraham Lincoln was elected President, North Carolina seceded from the Union in May 1861. During the Civil War the building was turned into a Confederate headquarters and hospital. The facility never re-opened as a Mint but, after the Civil War, from 1867 to 1913, it operated as a U.S. Assay Office. Today the structure houses an art museum. |

Unlike at the Philadelphia Mint where the roles of assayer and melter-refiner were separated, at the Charlotte Mint Dr. J.H. Gibbon had both jobs and was, when the Mint first opened, overwhelmed by the tasks. This caused a several month delay in minting the first coins because he simply couldn't do all the work by himself. Does this portray an unfamiliarity with his duties that would be implicit in a political appointment?

Gibbon remained the Assayer during the entire period the facility was a U.S. Mint and throughout the Civil War under the Confederacy.

The Assay process

During the assaying process, other metals like lead, copper and silver were extracted from the gold. When the metal was first melted it was poured into molds like those to the right. |

"In July 1838, worried about the chance of fire at Charlotte's Mint, one of its officials, John Heysham Gibbon, issued a warning. He reminded Superintendent John Wheeler Hill that the city operated only one fire truck, located far from the Mint. Gibbon suggested installing buckets and tanks to collect rainwater in and around the building. Hill partly complied, but one day disaster struck. On 27 July 1844 John Heysham Gibbon's gruesome prediction came true. Fire erupted at the Charlotte Mint and destroyed the stately building on Charlotte's West Trade Street. Gibbon had tried to warn Mint officials about the need for fire protection six years previous."

In the 1840 census of Mecklenburg county, North Carolina as John H. Gibbon. His household included had 1 boy under 5, 2 boys 10 to 15, and a man 40 to 50. Women in the housefhold included 2 girls under 5, 1 girl 5 to 10, and 2 girls 10 to 15, and a woman 30 to 40 years old. For an excellent history of the region, see History of Charlotte-Mecklenburg by Dr. Dan L. Morrill.

On 9 February 1842 in the House of Representatives, "Mr. Fillmore presented a petition of John H. Gibbons, praying to be allowed and paid 134 dollars for services rendered in transcribing, in part, the opinions of the Attorneys General, in answer to a resolution of the House of Representatives of the 23d March, 1840; which petition was referred to the Committee of Claims." Is this our John?

Gibbon, though born in Philadelphia, became more Southern in his outlook and opinions than the Southerners themsevles. On the eve of the Civil War, John is noted as being a "Democrat and a slaveholder." A footnote in Chapter XV of "The Church And Social Control," reads: For the Biblical justification of slavery by a North Carolina doctor, see J. H. Gibbon, "The Institution of Slavery in Accordance with the Principles of the Moral Law," DeBow's Review, XVI, 410-13. John Heysham Gibbon's opinions had moved very far from his Quaker forebears.

He appears to have been a writer on many subjects and was, as was typical of the era, an amateur naturalist. In 1845 J.H. Gibbon published an article, "Gold of North Carolina," in the American Journal of Science. In 1850 the Doctor found a meteorite "near the post office at Flows, 22 miles east of Charlotte." "An account of the principal circumstances attending the fall of the mass has been given by Dr. J.H. Gibbon, of the United States Branch Mint, Charlotte, N.C. . . ." - from "Summarized Proceedings . . . and a Directory of Members," by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He appears to have been a member of the Association. An article, "Meteorite in North Carolina," was published in the American Journal of Science. It was also published in the Philosophical Magazine and abstracted in 5 other scientific journals. John also wrote a paper "On some of the applications of Natural Sciences to the moral laws of ancient nations." He may have been a member of the American Philsophical Society as well. He presented a paper to them titled "Report on the Utility of a uniform System in Measures, Weights, Fineness and Decimal Accounts, for the Standard Coinage of Commerical Nations," 1854. He wrote three such historical papers on the subject.

I haven't yet been able to find the Doctor and his family in the 1850 census, though I do have Robert living on his own in a boarding house in Charlotte. Note that the first passenger train service did not reach Charlotte until 1852.

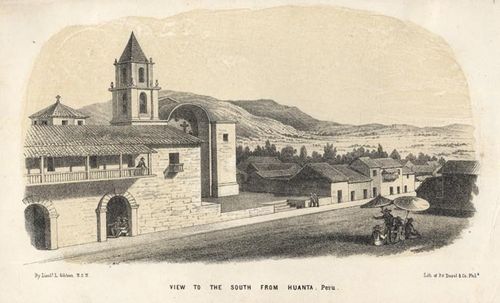

At about this time the Doctor's son, Lardner, returned from his expedition to South America. He apparently brought back some ancient relics with him. In "Prehistoric Man: Researches Into the Origin of Civilization in the Old and the New World," of 1862, its author, Daniel Wilson, remarks that "Dr. J. H. Gibbon, of the United States Mint, has favored me with the analysis of another chisel or crow-bar, brought from the neighborhood of Cuzco by his son, Lieutenant Lardner Gibbon, who formed one of the members of the Amazon Expedition."

In the 1860 census of Mecklenburg county, North Carolina as Dr. John Gibbon,a 65 year old. Living with him is Catherine, 62, Nicholas, 21, Margaret, 28, Catherine, 27, Mary 29 [?], Alice, 25, and Virginia, 20.

North Carolina seceded from the Union on 20 May 1861. The Charlotte Greys, a local Confederate unit, seized the Charlotte mint and turned it over to the Confederate States government on 27 June. As with the Federal mint at New Orleans, the employees resigned from federal employment, but kept their jobs once they swore allegiance to the Confederacy. The bullion kept by the mints was confiscated. Minting continued as before in New Orleans using Union dies. Though a new coin design was soon produced, the Confederate government decided that coins were "a waste of means and money," because they feared that there would not be enough bullion to produce circulating coinage, and that most of the coins produced would be exported and melted outside the nation. As a result the New Orleans Mint was ordered to suspend its operations and the South committed itself to a policy of paper money. Although the main Southern mint had closed, the desire to establish some sort of Southern metallic currency never died out. At one point John Gibbon, in his role as Assayer of the Charlotte Mint, suggested to the North Carolina Governor John W. Ellis, that their gold be used to make 1,000 five-dollar gold pieces bearing a unique state design. Nothing ever came from this suggestion because the Governor never took it seriously. All the southern mints were eventually converted into assay offices.

Gibbon attended a convention of Southern teachers during the war. Their self-described mission:

"Resolved, That this Association recommend a general convention of the teachers of the Confederate States, to be held at ----on----1863, to take into consideration the best means for supplying the necessary text-books for schools and colleges, and for uniting their efforts for the advancement of education in the Confederacy; and that the Executive Committee of the Association be directed to correspond with teachers in the various States on the subject." - from the "Proceedings of the Convention of Teachers of the Confederate States", Assembled at Columbia, South Carolina, April 28th, 1863.The following resolution was offered to the Convention by Dr. J. H. Gibbons, a member of the associattion for North Carolina:

"Resolved, That it be recommended by this Convention, to introduce the Constitution of the Confederate States as a text-book in all public schools." - from the "Ante-Bellum North Carolina: A Social History", Johnson, Guion Griffis, 1900- 1989.

During the war the Charlotte-Mecklenburg region was important strategically to the South. It had been a major railroad junction which, in time of war, transformed the region into a major manufacturing and distribution center for the South. The most important local facility was the Confederate Naval Yard, which produced mines, anchors, gun carriages, and marine engines. Other important facilities included a powder factory and the Mecklenburg Gun Factory, run by Dr. J.H. Gibbon.

"Prominent antebellum entrepreneurs invested in two new wartime industries: a powder-manufacturing company and a gun factory. Patriotic and profit-driven Charlotte entrepreneurs happily embraced the opportunity to take advantage of well-paying government contracts and the Confederacy's lucrative offer to subsidize powder and arms manufacturing. Local businesspeople, headed by lawyer S. W. Davis, established the North Carolina Powder Manufacturing Company on Tuckaseegee Road. That same year, William Phifer and J. M. Springs called a public meeting to form a joint-stock company to manufacture ordinance and shells. The company, noted the Western Democrat, was made up of "a goodly number of our wealthy and most influential citizens," who subscribed $15,000 for the factory. Dr. J. H. Gibbon served as president of the Mecklenburg Gun Factory, and the board included lawyer J. H. Wilson and planter A. B. Davidson." - from "Bittersweet Legacy: The Black and White "Better Classes" in Charlotte, 1850-1910" by Janette Thomas Greenwood, 1994.Note that a gun factory had been built in Mecklenburg as early as 1740. One of its guns was given as a gift to George Washington.

Several letters of John H. Gibbon, circa 1863.

"I have just received a letter from my youngest Son, Capt. Nicholas Gibbon, 28 Regt. N.C. Troops, in the General Hospital No. 8 in Raleigh, where he is obliged to remain for want of an extension of his furlough, that he may not be reported "absent without leave."

"I have just received a letter from my son Dr. Robert Gibbon, Senior Surgeon B. Gen. Lane's Brigade, dated 22 June, "in The Valley of Virginia, near Winchester," who writes, "If you think that it is necessary for an extension, all Nicholas has to do is to send Col. Lowe a physician's certificate, certified before a Justice of Peace, which I will approve for 30 days." - from "Papers" by William Alexander Graham, Max Ray Williams, Mary Reynolds Peacock.

The war ended in 1865. The local economy crashed, there was little hard currency left in circulation, and crime, especially theft, became rampant. Gibbon's future now depended on how the Federal government would treat those who had been in its employ, and then rebelled. In May 1865 Union troops occupied the region and their commander, Colonel Willard Warner, announced that ". . . all persons who wish to engage or are engaged in any business, are required to take the oath of allegiance to the United States." - from "The Civil War In Charlotte-Mecklenburg" by Dr. Dan L. Morrill.

On 29 December 1865 the President, Andrew Johnson, noted that "A commission having been granted during the recess of the Senate to John H. Gibbon as assayer of the branch mint at Charlotte, in the State of North Carolina, to fill a vacancy, I now nominate him to the same." On 29 January 1866 the nomination for a post unknown for a John H. Gibbon was referred to the Congressional Committee on Finance where it was tabled. On 26 June 1866 the President then nominated "Isaac Walter Jones, of Salisbury, North Carolina, to be assayer of the U. S. branch mint at Charlotte, in the State of North Carolina, vice J. H. Gibbon who cannot qualify." Then, on 6 March 1867 the President told the Senate that "I nominate Isaac W. Jones to be assayer of the branch mint at Charlotte, N. C., in place of J. H. Gibbon, who failed to take the oath, no action having been taken upon this nomination during the last session of the Senate." The Charlotte branch never reopened as a mint, but did operate from 1867 to 1913 as an Assay office with Mr. Jones in charge.

It is interesting that Gibbon, as a rebel and an old one at that, was even considered for this post. I had at first thought that he was not have been able to qualify simply due to his age. He was, afterall, 71 years old. However, it seems clear that the old rebel simply could not work for a Federal government he had so opposed - he would not take the oath.

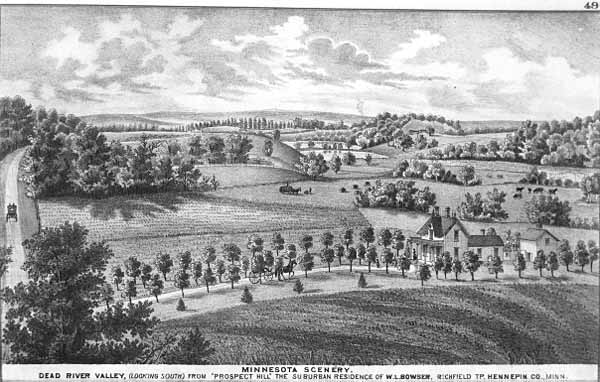

"An undated newspaper article of unknown origin, found in the Bible of William Heysham and his wife, Mary, put it this way:Those interests in archaeology and Indian tribes was probably spawned by both his trip to Panama and his son Lardner's adventures in South America.From his eminent fitness, as well as from these circumstances of fidelity to his trust, he was promptly reappointed to his former position. Here, with his old pursuits open to him, with the emoluments, more than ever before, needed in the wreck of Southern fortunes, the nice sense of honor of Dr. Gibbon found an insuperable obstacle. He refused to take the "iron clad oath." Many of his friends could not see the ground for his scruples. His age, his northern connection, his known sentiments as a Union man, had withdrawn him from any military or political connection with the rebellion. But the vague and comprehensive terms of the oath declare that the affiant has never given "aid or comfort to the enemy of the Constitution of the United States." Dr. Gibbon has passed his whole life in doing kindly offices to his fellow man, without regard to their political opinions. He would not take this oath, and he put from him the office that would have provided congenial employment for his declining years.

Such a man was Jack Gibbon's great-grandfather. With no means of support, Dr. Gibbon called upon one of his long-held interests, archaeology and extinct American Indian tribes, and planned to give lectures in various cities. He first visited Baltimore and it was there that his death occurred, on December 16, 1868. His remains were buried in the Elmwood Cemetery in Charlotte. The Charlotte branch of the Gibbon family survived; the Charlotte mint did not."

- from "A Dream of the Heart: The Life of John H. Gibbon Jr." by Harris B. Shumacker

John Heysham Gibbon died on 16 December 1868 and was buried in the Elmwood Cemetery, Charlotte, North Carolina. From "The Chicago Historical Society," page 161:

Gibbon, Dr. J. H., d. in Baltimore, Md. Dec. 16, 1868, a. 74; was a native of Philadelphia, but had lived south many years, and was the father of Maj. Gen. J. H. Gibbon.Baltimore was the home of John's estranged son, General John Gibbon, during the war. The General and his family were, however, out west at this time.

Catherine died on 20 December 1874 in Charlotte and was buried alongside her husband.

Their children were,

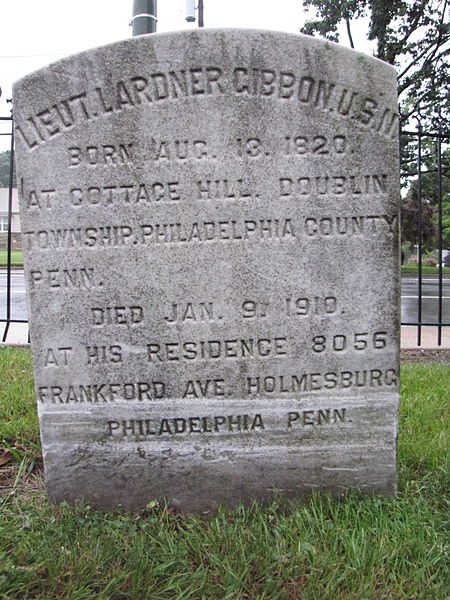

(23) Lardner A. Gibbon (1820)

(23) Dr. Robert Gibbon (1822)

(23) Mary Gibbon (c1825), unmarried

(23) General John Hannum Gibbon (1827)

(23) Catherine Gibbon (c1830)

(23) Anna Gibbon (c1833)

(23) Virginia Gibbon (c1835)

(23) Nicholas Biddle Gibbon (1837)

(23) Margaret Gibbon (c1838)

John H. Gibbon's first son, Lardner Gibbon was born on 13 August 1820 in the Holmesburg district of Philadelphia. His interesting first name was clearly a nod to the family of John's wife, Catherine Lardner Gibbon. I don't know what his middle initial stood for and there is a question whether he had a middle name at all. Lardner's younger brother, Nicholas Biddle, noted that his father disliked middle names and that he was the only child of the family to get one.

| Holmesburg

Present-day Holmesburg was the first area of Northeast Philadelphia to be developed into a town, originally called Washingtonville. Eventually the town took the name of the Holme family. Thomas Holme, William Penn's Surveyor General, and his son, John, were among the major early landholders. The village was located in Lower Dublin township. Lower Dublin Township was north of Township Line Road - now Cottman Avenue - from the River to the County Line, and north to Byberry and Moreland Townships. A year prior to the consolidation the township spilt in two. The eastern portion of Lower Dublin Township, including Holmesburg, became Delaware Township. Thanks to its great natural beauty and resources of the area, Holmesburg developed into a home for well-to-do families as well as an industrial outpost, with a grain mill, a calico print factory and a farming-tool manufacturing plant. In the 1830s, Philadelphia-born Shakespearean actor Edwin Forrest opened his home for aged actors there. The residents of the home -- some of the most renowned retired actors in the world -- would regularly stage plays for the local citizens. "Holmesburg was very aristocratic," Silcox said. "After the Civil War, you had four Union generals move in there." It lies near the Delaware river and was part of the 23rd Ward. For a fuller history, see Holmesburg. |

One of Lardner's earliest memories was of the week-long visit of Lafayette to the city. In 1824 President Monroe invited the 68 year old Marquis for a visit to the country he had helped make possible. Lafayette was received with wild adulation wherever he went. When asked by hosts how he wished to be introduced to his audiences, he replied,"As an American General." From 28 September to 6 October 1824 he visited Philadelphia, making an unforgettable speech at the State House, today's Independence Hall. Lardner remembered that he "had looked through the rails of the fence at the procession on that occasion as it passed by and recalled the hearty welcome way in which the famouse Frenchman received the guests at a reception near Holmesburg . . ." Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania was named in honor of the man and his visit. Lafayette died in 1834.

Lardner was appointed a midshipman in the U. S. Navy "when about 15 years of age," - from the United States Congressional Serial Set. I have a contrary reference that "Lardner Gibbon was appointed a midshipman on December 22, 1837. He was then 17 years 4 months and 9 days old." - from the "Bulletine of the Pan American Union" of 1910. The "Naval Register of the United States Navy, 1851" confirms this.

"Register of the Navy of the United States for 1851.I suppose the term "about" covered a lot of territory. This was in the period before his father's move to North Carolina when the family was still living in Philadelphia. In this era joining the Navy meant finding a ship's Captain who was willing to give you a berth on his ship. The ship's Captain, often deluged with such requests, would give priority to the sons of his relatives, his friends, other Captains, his superior officers, well placed officials, and his banker or his prize agent.

. . .

Passed Midshipmen (233).

Name, and Date of Entry.

. . .

L. Gibbon, 22 Dec. 1837." - from "The Life and Character of John Paul Jones" by John Henry Sherburne, 1851

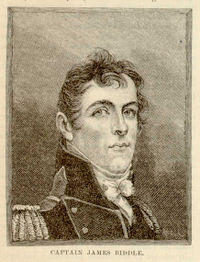

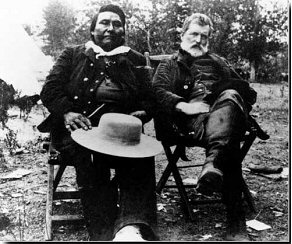

While John H. Gibbon had just finished a term in the Pennsylvania Assembly and was not without clout, Lardner's most likely ally in finding a post was Commodore James Biddle, right. The Biddle's were related to the Gibbon's through the Shepard family. The Commodore's mother, Hannah Shepard, was the sister of John H. Gibbon's mother-in-law. The Commodore had been the commander of the Mediterranean and South American squadrons and, in 1835, he was in charge of the nearby Philadelphia Naval Yard. From 1838 to 1842 he was the Governor of the Naval Asylum, a hospitial in Philadelphia. It was at his suggestion that midshipmen who had not yet passed their rating exams were sent to the Asylum for instruction, laying the foundation for the Naval Academy. Note too that the Charles Biddle that John H. Gibbon accompanied on his expedition to Panama was the Commodore's brother.

While John H. Gibbon had just finished a term in the Pennsylvania Assembly and was not without clout, Lardner's most likely ally in finding a post was Commodore James Biddle, right. The Biddle's were related to the Gibbon's through the Shepard family. The Commodore's mother, Hannah Shepard, was the sister of John H. Gibbon's mother-in-law. The Commodore had been the commander of the Mediterranean and South American squadrons and, in 1835, he was in charge of the nearby Philadelphia Naval Yard. From 1838 to 1842 he was the Governor of the Naval Asylum, a hospitial in Philadelphia. It was at his suggestion that midshipmen who had not yet passed their rating exams were sent to the Asylum for instruction, laying the foundation for the Naval Academy. Note too that the Charles Biddle that John H. Gibbon accompanied on his expedition to Panama was the Commodore's brother.

There were many other members of the family who were also in the Navy and might have either helped Lardner find a place or influenced his decision to join. The Navy was "in the blood" so to speak. James Lawrence Lardner on his mother's side of the family would rise to an Admiral's rank in the Civil War. Born in 1802, he was 18 years older than Lardner Gibbon and may have influenced Lardner's decision, though he was perhaps too junior in 1835 to find Lardner a midshipman's berth. The Commodore's son, James Stokes Biddle, had been found a berth in 1833, just four years before Lardner and his process of finding a posting may have attracted Lardner's attention, or that of his father's.

However, note that young Lardner's first posting was to the West Indian squadron, operating out of Pensacola, Florida. His uncle, Commodore James Biddle, had been the commanding officer there in 1822. Young captains would have been all too eager to accomodate this senior officer by taking his nephew aboard.

15 [if he did in fact join in 1835] was a not uncommon age to commence a naval career. William Herndon, mentioned below, also became a midshipman when he was 15 years old. Lardner's parents would have procured a sea chest for the lad with all the necessaries, including the regulation uniform, white ducks, white vest, and navy-blue pea jacket properly decorated with brass buttons and midshipman's insignia. He would also have a visored cap and a dirk attached by a gilt chain to the blue webbing belt around his waist.

Lardner would have, most likely, been ordered to a ship almost immediately. Unlike the Army which first taught its young officers the basics at the Military Academy at West Point, the Navy believed the best school was the deck of a ship at sea. The Navy kept ships on station in the West Indies, off the eastern seaboard of South America and in the Mediterranean, as well as off the coast of the United States.

"He was assigned to the West Indian Squadron on January 23, 1838 . . ." - from "United States Congressional Serial Set." Ships in the squadron in 1838 included the frigate CONSTELLATION, sloops BOSTON, CONCORD, LEVANT, ST. LOUIS, and VANDALIA.

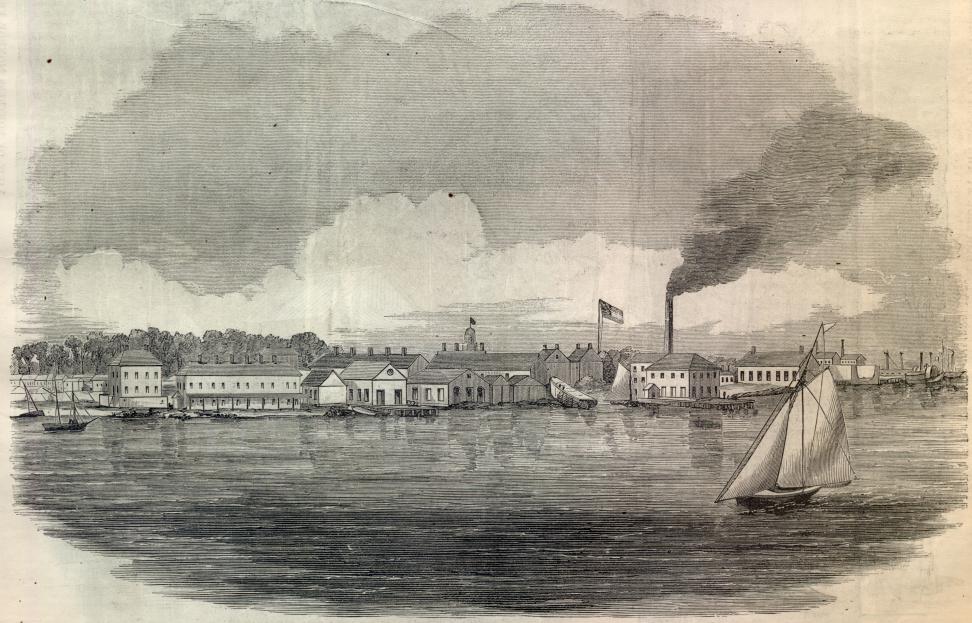

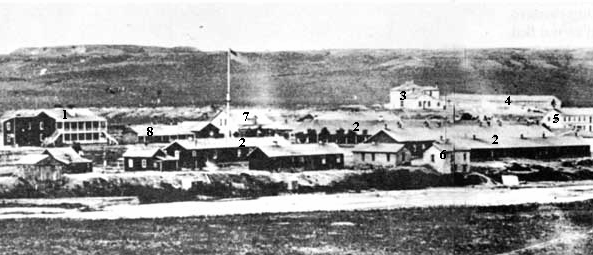

| The West Indian Squadron

The squadron was based at Pensacola, Florida, which is located just east of Mobile, Alabama. It had been established in 1822 under the command of Commodore James Biddle to control piracy and defend trade. The area they were responsible for was vast, including all of the area from the tip of West Africa to the Gulf of Mexico. In 1838 its commander was Willian Branford Shubrick. During this period the Navy assisted the Army in Florida during the Second Seminole War and helped suppress the slave trade, which had been outlawed by the US Congress. Below is the Navy Yard at Pensacola in about 1860, seen from across the bay, at Fort Pickens.  |

Midshipman Gibbon was assigned to the frigate CONSTELLATION.

"Navy.

Orders.

Jan. 23--Mid. Lardner Gibbon, W.I. squadron." - from "The Army and Navy Chronicle" of 1838, page 80. . . .Pensacola, May 12. "The frigate Constellation, bearing the broad pennant of Com. Dallas, sailed on Wednesday morning last, for Tampico and thence to Vera Cruz.

The following is a list of officers attached to the CONSTELLATION. Commodore, A.J. Dallas; Flag Captain, J.M. McIntosh; . . . Midshipmen: . . . Lardner Gibbon . . . " - from "The Army and Navy Chronicle" of 1838, page 347

. . .2 October 1838, Pensacola, Florida. "The U.S. frigate Consellation sailed from this harbor, on Tuesday the 2d inst. Her destination is Boston. The following is a list of the officers of the frigate.

James M. McIntosh, Esq., Commander; . . . L. Gibbon [Midshipmen] . . ." - from "The Army and Navy Chronicle" of 1838, page 269

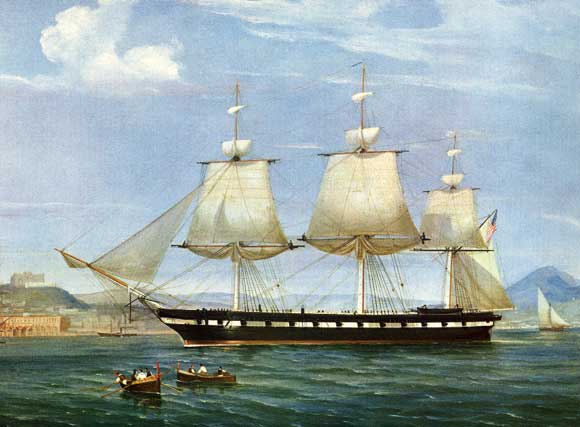

| Frigate CONSTELLATION

"In October 1835, Constellation sailed for the Gulf of Mexico to assist in crushing the Seminole uprising. She landed shore parties to relieve the Army garrisons and sent her boats on amphibious expeditions. Mission accomplished, she then cruised with the West India Squadron until 1838 serving part of this period in the capacity of flagship for Commodore Alexander Dallas." - from DANFS CONSTELLATION was disassembled in 1854, by then almost 60 years old, her hull twisted and hogged, and some of her parts were used in the construction of the sloop of the same name. |

In January 1839 CONSTELLATION was put into the Norfolk [?] yards for a refit and Midshipman Lardner was ordered to join the ST. LOUIS, then in New York City where it was just coming back into commission after having been laid up in ordinary.

"He [Lardner] was assigned to . . . the St. Louis from 1839 to 1842." - from "United States Congressional Serial Set"The sloop-of-war ST. LOUIS sailed under the command of Command French Forrest to join the Pacific Squadron at Monterey, California via Cape Horn.

| USS ST. LOUIS

The first Navy ship to bear the name, she was a three masted vessel built at the Washington Navy Yard and launched on 18 August 1828. A 700-ton sloop-of-war, she had a complement of 125 and was armed with 18 to 20 24-pound guns. A sloop-of-war carried all of her guns on one-deck only. ST LOUIS had been part of the West Indian squadron, operating out of Pensacola, Florida from 1832 to 1838, largely as flagship for the squadron, cruising the Caribbean. On 28 May 1838, she sailed from Havana for New York where she placed "in ordinary," that is out of commission, on 1 July and laid up until 5 April 1839. On 30 June 1839 she sailed under the command of Commander French Forrest to join the Pacific Squadron at Monterey, California. She stopped at the Cape Verde islands, Rio de Janeiro, and various ports on the Pacific coast of South and Central America. Below is a watercolor of the ST. LOUIS by Moses Lane, a Navy gunner, during the sloop's Mediterranean cruise of 1852-1855.  |

Onboard ST LOUIS Lardner would have begun "to learn the duties of a seaman by firsthand experience; sails and ropes, knotting and splicing, charting a course, the lore of the sun and stars, the winds and currents, steering, and gunnery. He went aloft with the crew, but he also learned the duties of command in anticipation of advancing someday to the quarterdeck." - from "High Seas Confederate," the story about a young midshipman who also served onboard the ST LOUIS in the 1830's.

The ship would have made the transit into the Pacific via the dangerous waters of Cape Horn. Lardner mentions in his "Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon" about the Indians he had met that "Many of their expressions in Quichua sound like the language of the natives of the South Pacific islands, as I recollect it ten years ago, while cruising as a midshipman in the ship-of-war St. Louis."

In another quip about Navy life from his book, Lardner says "We saw here what we had before seen at a midshipman's mess--one man cunningly eating another man's allowance."

| French Forrest

Captain Forrest was a forward thinking man and shared the general desire in the Navy to create a training program for sailors. He established onboard a school to make boys into apprentice seamen. He had the ST LOUIS "rigged entirely by apprentice boys . . ." - from "The Story of the United States Navy" by Benson John Lossing. This was a widely shared idea at the time, but one which failed because so many of the boys taken as apprentices were confused about the program, thinking that they would become midshipmen, not sailors. This failure however helped lead to the founding of the Naval Academy. |

In 1839, and I suppose while enroute to her duty station, ST LOUIS was in the port of Callao, Peru when the country's President, General Agustin Gamarra, was forced to flee opposition forces. He sought and received asylum onboard ST LOUIS. Four years later he attempted to return to office, was unsuccessful and fled to the USS FAIRFIELD in Callao Bay. One of ST LOUIS' boatswain's mates at this time, John J. Chase, had been a ship-mate of Herman Melville on the USS UNITED STATES. He deserted to join the Peruvian revolution.

| The Pacific Squadron

This squadron, also known as the Pacific Station, had been established in 1821. Its responsibilities included the entire west coast of North and South America, and the Hawaiian and Society islands. Its mission was the protection of commerce. Its issues were revolution in South America, tense relations with Mexico, which rightly feared American intentions in California, and the unsettled question of the Oregon territory. Commodore Alexander Claxton had been ordered to the Pacific in 1839, relieving Commodore Ballard. It is conceivable that he came in the ST LOUIS. The USS CONSTITUTION was the squadron's flagship. Claxton died in CONSTITUTION while in Chilian waters on 7 March 1841 and was succeeded by Captain Thomas ap Catesby Jone, who brought out the USS UNITED STATES in 1842 to replace CONSTITUTION. |

In 1840 Mexican officials at Monterey had imprisoned 40 British and American citizens for alleged spying. The newly-arrived ST LOUIS was sent to intecede. Unfortunately the ship soon sailed again and little was accomplished. The release of the Americans did not occur until 1841.

In February 1841 ST LOUIS was in Nukahiva, in the Marquesas "ascertaining the sentiment of the Natives towards our whale fishery-men." Captain Forrest broke up a local war between two pilots that had closed one of the bays to the whalers. The Marquesas are part of French Polynesia, just northeast of Tahiti, in the Society islands. ST LOUIS also visited Honolulu in Hawaii. Late in the year she became the first American man-of-war to enter San Francisco bay.

She was relieved by the USS DALE and returned to Norfolk on 15 September 1842 where she was laid up in ordinary again.

"In 1842 and 1843 he [Lardner] attended the naval school in Philadelphia, stood his examinations, and was warranted a passed midshipman on July 12, 1843." - from "United States Congressional Serial Set." The Naval Historical Center indicates he made this rank on 29 June 1843. Note that Commodore James Biddle, a near relation on the maternal side of Lardner's family, was still Governor of the Asylum in 1842.

| The Naval Asylum

While the U. S. Naval Academy at Annapolis was not established until 1845, it had been recognized early in the Navy's history that the training of officers needed to be addressed formally. In 1802 the education of midshipmen was resolved by instructing them aboard ships at sea with chaplains as schoolmasters. The need to provide instructions in mathematics and navigation led to the authorization in 1813 of civilian schoolmasters, and teachers of these areas, eventually appointed as professors of mathematics. By the early 1830s "cram schools" were operating in three states and beginning in 1838 midshipmen approaching examinations for promotion, were assigned to a naval school in Philadelphia for 8 months of study. For an understanding of what the life of a midshipman at-sea might have been like, read the novels of C.S. Forester and Patrick O'Brian.

|

| 19th Century Navy Rank Structure

The rank system prior to 1862 was: Midshipman, Passed Midshipman, Master, Lieutenant, Commander, and Captain. After 1862 it became: Ensign, Master, Lieutenant, Lieutenant Commander, Captain, Commodore, Rear Admiral. |

"He [Lardner] served successively on a receiving ship at Norfolk, Virginia, on the On-ka-Hy-e, on the Boston, and at the Naval Observatory . . ." - from "United States Congressional Serial Set." Here the term "successively" appears to mean "in quick rotation" for at least the first two units, because on 27 October 1843, just three months after he finished the naval school, the BOSTON left Boston harbor for the Brazilian station.

| USS ON-KA-HY-E

|

Transferring from the unnamed receiving ship, Lardner may have been assigned to ON-KA-HY-E only during her time in the yards. This would make sense if he transferred to BOSTON during the latter's possible stop in Norfolk, or Charleston, enroute to station. If BOSTON was short of men, say a midshipman fell ill and had to be left behind, as a ship departing on a cruise she would be given her pick of the men in port.

The Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript and Special Collections Library has the papers of Lardner Gibbon from 1843 to 1848. The collection includes a diary, chiefly from the period when Gibbon was off the coast of South America on board USS BOSTON while the Navy was protecting U.S. interests during the conflict between Uruguay and Argentina. Also included are daily accounts given during part of the siege at Veracruz, Mexico during the Mexican-American War.

| The Uruguayan War Against Argentina

In 1839 President Rivera, with the support of the French and of Argentine emigres, issued a declaration of war against Argentina's dictator, Juan Manuel de Rosas. The French, however, reached an agreement with Rosas and withdrew their troops from the Rio de la Plata region in 1840, leaving Montevideo, in Uruguay, vulnerable. For three years the locus of the struggle was on Argentine territory. However, in 1842 Rivera was defeated and, in 1843, Argentine forces laid siege to Montevideo. This siege was to last for nine years. The intervention first of France, from 1838 to 1842, and then of Britain and France, from 1843 to 1850, transformed the conflict into an international war. First, British and French naval forces temporarily blockaded the port of Buenos Aires in December 1845. Then, the British and French fleets protected Montevideo at sea. |

USS BOSTON's role off the coast of South America was probably to observe the movements of the foreign fleets and to be prepared to offer assistance to the embassy and American citizens ashore, as required. The frigate CONGRESS was also on-station. I suspect she hosted the flag, Commodore Daniel Turner. He had been the captain of the CONSTITUTION, on the Pacific station, while Lardner was on the ST. LOUIS.

| USS BOSTON

BOSTON was back in Boston early in August 1843 and was put out of commission. She was recommissioned on 27 October 1843 under the command of Commander Garrett J. Pendergrast, right. Soon thereafter she joined the squadron on the Brazil Station where she remained from 1843 to 1846. She returned to the United States and was placed out of commission for repairs in the New York Navy Yard on 10 February 1846. She completed repairs in the fall and was then ordered to join Commodore David E. Conner's Home Squadron, blockading the Mexican east coast. While enroute to her new station, under the command of Commander George F. Pearson, USS BOSTON was wrecked on Eleuthera Island, in the Bahamas, during a squall in November 1846. Her crew was saved, but the ship was totally destroyed. |

Captain Pendergrast of the BOSTON had a sharp difference of opinion with the charge d'affaires at Buenos Aires, William Brent, on the blockade of Montevideo by the Argentine Navy in 1845. Brent wanted the US Navy to comply with the blockade while Pendergrast insisted on his right to break the blockade, as the French had, if he needed to replenish his ship. Pendergrast did subsequently break the blockcade and was reprimanded by the Secretary of the Navy.

The BOSTON came back to America from the Brazil Station and entered the yards at New York City for extensive repairs from February to November 1846.

I had misread this before, but the "United States Congressional Serial Set" clearly stated that Lardner went to the Naval Observatory after his tour on the BOSTON. While I thought that meant in 1848, it is now apparent that he had two tours at the Observatory, the first being in 1846.

At the Observatory Lardner became acquainted with its superintendent, Lieutenant Matthew Maury, the Navy's Oceanographer - from "Matthew Fontaine Maury: Scientist of the Sea" by Frances Leigh Williams, 1963. Another source claims that Lardner became a "protege" of Maury. Lardner would also have met Lieutenant William L. Herndon, Maury's brother-in-law. Herndon had been attached to the Depot of Charts and Instruments, later to become the Naval Observatory, from 1842 to 1846. It was in about 1845 that Maury was making his first astronomical observations. William Herndon was the permanent observer for the prime vertical telescope. - from "Sky and Ocean Joined: The U.S. Naval Observatory 1830-2000" by Steven J. Dick.

| The Naval Observatory

Its primary mission was to care for the U.S. Navy's chronometers, charts and other navigational equipment, such as sextants, barometers, and thermometers. It is also the repository of all ship's logbooks. The time ball, shown at the top of the observatory, left, was one of the first systems to enable the Observatory to support remote users. The ball was dropped at established times, which enabled ships anchored in the Potomac River to calibrate their chronometers. The building depicted was completed in 1844.

|

I don't know how or why Lardner got these orders; they do not fit in the natural progression expected of a naval officer. He should have gone back to sea. If nothing else it meant that Lardner's mastery of mathematics & navigation was strong. His new boss, Lt. Maury, had, afterall, written the official Navy handbook on the subject, titled "Navigation."

Three Lieutenants and six Passed Midshipmen were assigned to duty at the Observatory, in addition to three Navy Professors of Mathematics and assorted civilian workers. Lardner's duties would have included collating the incoming meteorlogical and hydrographic data recorded by naval ships, compiling and correcting charts, periods at the great telescopes observing the night sky and cataloguing the stars, and mathematical computations, or reductions, that had to follow the astronomical observations. He also learned drafting skills which he would later use creating the maps from his South American expedition.

In 1846 war broke out between Mexico and the United States. The officers at the Observatory immediately began to campaign for sea-duty orders; no one wanted to miss the chance for fame and promotion.

| The Mexican-American War

Friction between the United States and Mexico, aggravated by an ever-increasing American population in the southwest and admission of the Texas Republic into the Union, resulted in war in 1846. The Navy's Home and Pacific Squadrons blockaded the enemy's east and west coasts, and seized numerous ports. |

Early in 1847 Lardner was ordered to the frigate, USS CUMBERLAND, then in Norfolk completing repairs. The ship was ordered to the waters off Vera Cruz, Mexico.

| USS CUMBERLAND

The CUMBERLAND, a 54-gun frigate, was built over an extended period, from 1825 to 1843, at the Boston Navy Yard. She had a complement of 400 men. She was commissioned in November 1843 and her first service was as flagship of the Mediterranean Squadron from 1843 to 1845. She was several times flagship of the Home Squadron between February 1846 and July 1848, serving in the Gulf of Mexico during the Mexican War. She was initially under the command of a Captain Dulany, but he had fallen ill soon after reaching Vera Cruz and was replaced by Captain French Forrest, who had been captain of ST. LOUIS when Lardner was onboard. On 28 July 1846 CUMBERLAND ran aground while off the point of Anton Lizardo and, while not seriously damaged, she returned to Norfolk in December, under the command of Captain Francis H. Gregory of the RARITAN, to have her copper bottom replated. The officers and crew of the two ships were also swapped, with the RARITAN becoming the new flag ship. Note that CUMBERLAND and RARITAN were very similar ships making this crew swap relatively easy. CUMBERLAND later returned to Mexican waters, probably early in 1847. After the war she returned to the United States via Havana, and was in New York City by July 1848. By this time Captain William Jamesson had assumed command.

"U.S. Frigate Cumberland, 54 Guns. The flag ship of the Gulf Squadron, Com. Perry." She was later modified by removing her spar-deck, that is, she was razeed, to carry a smaller number of heavier guns and redesignated a 32-gun sloop. During the Civil War she was part of the blockading fleet, anchored off Newport News, Virginia, under the command of Captain Pendergrast, whom we last met as Captain of the BOSTON. In March 1862 the Confederate ironclad, VIRGINIA, rammed and sank the Union frigates CUMBERLAND and CONGRESS. |

In 1847, assumably at the same time Lardner got his orders, Lt. James Harmon Ward was given command of CUMBERLAND, which would again became flagship of the Home Squadron off Veracruz, now under Commodore Matthew C. Perry. Harmon had taught at the Naval Asylum School at Philadelphia and may have known Lardner as a student there.

| James Harmon Ward

In 1847 he took command of the frigate CUMBERLAND during the Mexican-American War. He has the sad distinction of being the first officer of the US Navy to be killed during the Civil War. He wrote two books, "An Elementary Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery" and "A Manual of Naval Tactics," and a popular treatise on steam engineering. Matthew Calbraith Perry

Perry's most famous accomplishment, however, was the opening of Japan in 1852-1854. He subsequently wrote a 3-volume report on the expedition. He died in 1858. |

Lardner was joined onboard the CUMBERLAND by his Naval Observatory shipmate, William Herndon.

"During the Mexican war he [Lt. William Herndon] applied for orders, and was appointed to the frigate CUMBERLAND. He proceeded to Norfolk, and had embarked, when his destination was changed. Commodore Perry, then in the Gulf, had applied to the Department to send out to him an active and intelligent officer, who could speak the Spanish language, to be placed in command of a small steamboat . . . " - from "Monthly Nautical Magazine, and Quarterly Review."This steamboat was the IRIS.

"Propelled by radial paddle wheels, Iris built at New York in 1847 and purchased there by the Navy in the same year. She commissioned at New York Navy Yard 25 October 1847, Commander Stephen B. Wilson in command. The next day Iris departed New York Harbor for Vera Cruz, Mexico, where she arrived 11 December. With the exception of a brief visit to Mobile, Alabama, in February 1848 and a voyage to Pensacola, Florida, in September, Iris remained on duty in the vicinity of Vera Cruz for the next year. During the closing months of the Mexican-American War, she assisted in maintaining the blockade of the coast of Mexico and protected the Army's water communications. Thereafter she vigilantly protected United States interests in that volatile area lest trouble break out anew. Iris departed Vera Cruz 8 November and arrived Norfolk, Virginia 16 December. She decommissioned there 16 December 1848 and was sold soon thereafter. She redocumented as Osprey 9 March 1849, being destroyed by fire at Kingston, Jamaica, 18 April 1856." - Wikipedia"In this small vessel he remained till the close of the war, often performing tasks of much difficulty and danger, but with uniform skill and success." - from "Monthly Nautical Magazine, and Quarterly Review."

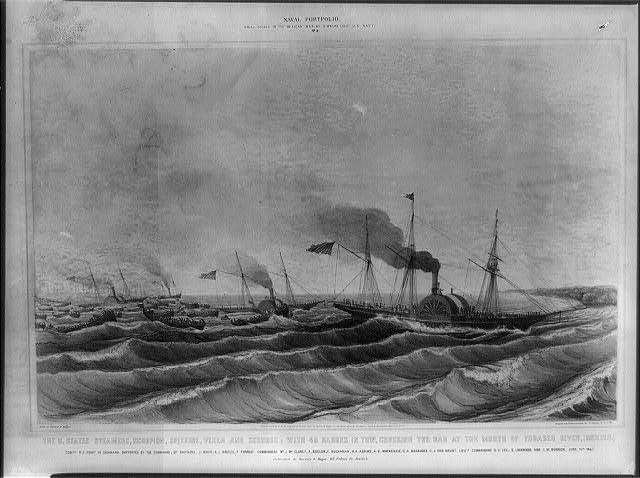

Lardner was assigned to the steamship SPITFIRE as acting Master, probably upon arriving off Vera Cruz onboard the CUMBERLAND. The SPITFIRE's executive officer was Lieutenant David Porter, another of Maury's followers at the Naval Observatory. At the outbreak of the war, however, Porter was just coming off a mission to Haiti. Upon arriving in Vera Cruz he was assigned to the SPITFIRE, under the "peppery, impulsive" Commander Joshua Tattnall. Porter later gained fame in the Civil War, becoming the Navy's first Full Admiral.

| SPITFIRE

On 19 May 1846, only six days after President Polk signed the Declaration of War with Mexico, Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft authorized the purchase of Spitfire and Vixen, two light draft steamers being built for the Mexican Navy. The ships were delivered to the United States Navy on 14 July 1846, and Spitfire was commissioned on 21 August 1846, Commander Josiah Tattnall in command, Lt. David Dixon Porter executive officer. The SPITFIRE was a two-masted sidewheel steamer designed for inshore operations. She was poor under sail, making as much leeway as headway in a stiff breeze, and shipped a great deal of water in rough seas. After a period carrying dispatches, she joined the American blockage off Vera Cruz on 10 November 1846. Commodore David Conner used her as his flagship for the attack on the port of Tampico. Two days after the town's capitulation, boats from Spitfire and Vixen ascended the Panuco river and captured three small Mexican gunboats. On the 18th, Spitfire and schooner Petrel went further up the river and captured the town of Panuco. They also destroyed nine Mexican 18-pounders, threw a large supply of 18-pound shot in the river, and burned military stores before heading downstream on the 21st. On 13 December, Connor departed Tampico in the USS Princeton and left Commander Tattnall in charge there until enough Army troops arrived to hold the town. Spitfire did not return to Vera Cruz until 3 January 1847. |

| The Battle of Veracruz

The Army had decided that the best way to end the war was to take Mexico City, and the best route there was through the city of Vercruz. Commodore David E. Conner had concentrated a naval force off the city which consisted of three frigates, the CUMBERLAND and RARITAN, which shared flagship duties, and the POTOMAC, four sloops-of-war, FALMOUTH, JOHN ADAMS, ALBANY, and ST. MARY'S, four screw steamers, MISSISSIPPI, which was Deputy Commodore Matthew Perry's flagship, PRINCETON, SPITFIRE, and VIXEN, brigs, SOMERS, PERRY, TRUXTON, and PORPOISE, schooners FLIRT, REEFER, PETREL and BONITA, and store-ship RELIEF. General Scott brought the USS MASSACHUSETTS, a wooden steamer, as his flagship. Later the ship-of-the-line OHIO was brought in to assist in the assault on the fort of San Juan de Ulua. - from "The Home Squadron Under Commodore Conner in the War with Mexico" by Philip Syng Physick Conner.

SPITFIRE led a flotilla of gunboats and other light draft naval vessels close to the shore to support the landing of Army troops who began to invest the city. The next day SPITFIRE anchored east of the Mexican fortress at San Juan de Ulloa and opened fire on the castle to divert the attention of the Mexicans from General Winfield Scott who shifted his headquarters ashore that morning. After an engagement lasting about 30 minutes, SPITFIRE withdrew out of range of the Mexican cannon. The days that followed were devoted to preparations for a siege of the city. At mid-afternoon on the 22nd, when the cannonading began, SPITFIRE led Tattnall's flotilla in an attack on the shore end of the city walls and maintained the bombardment until dark. The steamer's fire was praised as being especially accurate and effective. During the action, the batteries in the fortress fired on the flotilla, but its ships were undamaged. That night, SPITFIRE's executive officer, Lt. David Dixon Porter, made a daring boat reconnaissance of the harbor at Vera Cruz to locate the best position for the flotilla when it resumed its shelling. The next morning, Tattnall sailed his gunboats within grape-shot range of Fort Santiago and opened fire on both the town and the fort. The Mexican guns replied but were unable to depress their pieces sufficiently to hit the fearless American gunboats. By the 15th Veracruz was surrounded. On March 22 after the town refused to surrender Scott began an cannonade of the town. Army cannons, however, were too light to break through the walls. Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who had just relieved Conner, suggested using the heavier Navy cannons with Navy gun crews. The battery was laid out under the direction of Captain Robert E. Lee. After twelve days of firing the Mexicans agreed to surrender. American forces occupied the town on 29 March 1847. General Scott then led his forces on to the Mexican capital. The war ended in 1848. |

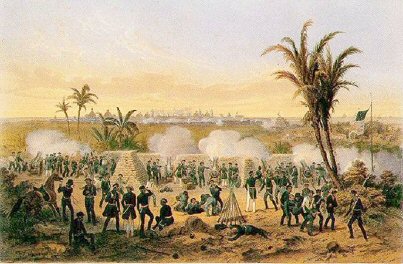

After the amphibious landing at Veracruz was successfully completed, Matthew Perry relieved Conner as Commodore. He offered General Winfield Scott 6 heavy naval guns manned by sailors from the ships to help break the walls of Vera Cruz during the siege that began in March 1847. These included two 32-pounders from the POTOMAC, one 32-pounder from the RARITAN, and one 8-inch shell gun (68-pounder) each from MISSISSIPPI, ALBANY, and ST. MARY'S. These were landed at night with double crews, the junior officers casting lots for the service. The illustration to the right shows the high and commanding position of the naval artillery and a the full view of the city under bombardment. The position was under the command of a young Robert E. Lee. The naval officer present included Smith Lee, Robert's brother, and Raphael Semmes who later commanded the Conderate ironclad, ALABAMA [Semmes was Conner's flag officer onboard CUMBERLAND and later RARITAN]. Gun crews from the fleet took turns serving the pieces. All the Navy men complained about fighting ashore and the necessity of digging-in and building revetments. One officer told Robert E. Lee, "I suppose the dirt did save some of my boys from being killed or wounded," but I have "no use for dirt banks on shipboard--that there what we want is clear decks and an open sea. And the fact is, Captain, I don't like this land fighting, anyway. It ain't clean!" Lardner Gibbon may have been attached to the Naval battery during the siege. This would account for him being ashore to provide "daily accounts given during part of the siege at Veracruz." I suppose I may be making too much of this statement. He could have made daily accounts while bombarding Vera Cruz from the decks of the SPITFIRE as well.

After the amphibious landing at Veracruz was successfully completed, Matthew Perry relieved Conner as Commodore. He offered General Winfield Scott 6 heavy naval guns manned by sailors from the ships to help break the walls of Vera Cruz during the siege that began in March 1847. These included two 32-pounders from the POTOMAC, one 32-pounder from the RARITAN, and one 8-inch shell gun (68-pounder) each from MISSISSIPPI, ALBANY, and ST. MARY'S. These were landed at night with double crews, the junior officers casting lots for the service. The illustration to the right shows the high and commanding position of the naval artillery and a the full view of the city under bombardment. The position was under the command of a young Robert E. Lee. The naval officer present included Smith Lee, Robert's brother, and Raphael Semmes who later commanded the Conderate ironclad, ALABAMA [Semmes was Conner's flag officer onboard CUMBERLAND and later RARITAN]. Gun crews from the fleet took turns serving the pieces. All the Navy men complained about fighting ashore and the necessity of digging-in and building revetments. One officer told Robert E. Lee, "I suppose the dirt did save some of my boys from being killed or wounded," but I have "no use for dirt banks on shipboard--that there what we want is clear decks and an open sea. And the fact is, Captain, I don't like this land fighting, anyway. It ain't clean!" Lardner Gibbon may have been attached to the Naval battery during the siege. This would account for him being ashore to provide "daily accounts given during part of the siege at Veracruz." I suppose I may be making too much of this statement. He could have made daily accounts while bombarding Vera Cruz from the decks of the SPITFIRE as well.

| The SPITFIRE

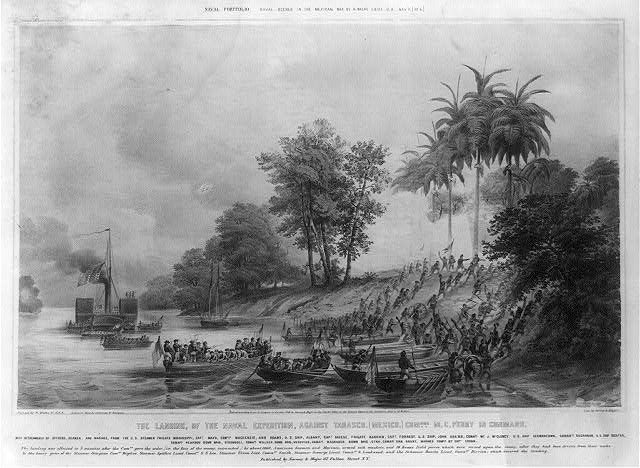

After the surrender of Vera Cruz, Spitfire participated in the expedition against Alvarado and the capture of Tuxpan as Commodore Matthew C. Perry's flagship. Sometime before the action at Tabasco, described below, David Porter took command of Spitfire.

On 14 June, she was part of the force which took Frontera at the mouth of the Tabasco River.