|

Mexican Land Grants |

|

|

Mexican Land Grants |

|

| Links: El Presicio Real de San Diego | Mission San Diego de Alcala | Kumeyaay History | Archaelogical Research at Los Pensasquitos Ranch | |

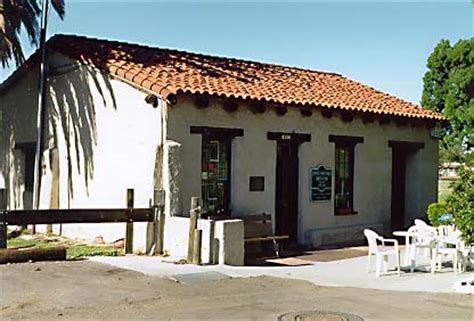

The Los Penasquitos adobe is located at 12122 Canyonside Park Drive in the Los Penasquitos Canyon Preserve. San Diego County Park docents lead a free guided tour of Rancho Santa Maria de Los Peñasquitos at 11:00 am on Saturdays and 1:00 pm on Sundays. Tours last 45 minutes.

The region now known as San Diego county was originally settled by the San Dieguito people, followed later by the La Jollan and the Yuman/Kumeyaay. The site of the Penasquitos adobe, close to a seasonal creek and several natural springs, shows evidence of native occupation for the last 7,000 years.

The region now known as San Diego county was originally settled by the San Dieguito people, followed later by the La Jollan and the Yuman/Kumeyaay. The site of the Penasquitos adobe, close to a seasonal creek and several natural springs, shows evidence of native occupation for the last 7,000 years.

The Spanish had claimed the region in 1542 when Captain Juan Rodriquez Cabrillo landed on the bay. The region received its name later, from Captain Sebastian Vizcaino, who was mapping the coast in 1602. The day Vizcaino came upon the bay was the Saints' Day of San Diego de Alcala, who was also the patron saint of his ship, thus earning the region that name. However, the Spanish did not seek to physically occupy Alta California until the middle of the 18th century when they did so to counter English explorers and Russian fur traders who were working their way down the coast into northern California. On 16 July 1769 a Spanish exploration party commanded by Governor Gaspar de Portola, under the religious leadership of Father Junipero Serra, arrived by the overland route to San Diego to secure California for the Spanish crown. The explorers established a presidio and a co-located mission on the San Diego river where it curved south towards San Diego bay. This was just above where the native village of Kosa'aay lay (note: the map to the right is oriented East, north is to the left). Canada de San Diego means Canyon or Valley of the San Diego [river]. In 1774 the Mission San Diego de Alcala was relocated 6 miles up that valley to be closer to a reliable source of water and more fertile land, and away from the bad influence of the soldiers. Pueblo de San Diego refers to the Mexican town founded in a later decade. I wonder what Muerto, 'dead,' refers to? A grave yard? Seems a long way off.

Most of the region's arable land was given to the Mission San Diego de Alcala for grazing and agriculture, and to support their religious mission of converting the natives. In theory the missions held the land in trust. By law, the land was supposed to pass back to the native population after a period of about ten years, when the padres' work of instruction and conversion were complete. The natives would then become Spanish subjects. This never occurred.

| Spain in Alta California

In 1769 Don Gaspar de Portolá led the military forces and Franciscan Fray Junípero Serra led the forces of the church, constructing a string of missions, presidios and pueblos up the California coast. San Diego was the first base for this expedition. The El Camino Real, a 600 mile long road, was constructed to link all 21 missions established in Alta California, from San Diego to Sonoma. |

The name Penasquitos is first mentioned in a map of San Diego dated 1800. The Penasquitos valley was Mission land and the Padres planted vinyards and orchards there, and grazed sheep. These would have been tended by native converts. It was at this time that the first structures were built. Archaelogical evidence indicates that a well, now known as the Spansih well, a tiled channel, or zanja, and possibly the springhouse and pond were constructed by the Padres. These would have been necessary to irrigate the crops. An adobe dwelling for the property's caretakers may have also been built.

The Mexican Revolution, 1810-1821, freed Mexico from Spanish control. In the turbulent decades that followed the northern territories, including Alta California, were generaly ignored by Mexico City.

To break the land monopoly of the missions the new Mexican government passed the Secularization Act of 1833 which repossessed the lands that had been granted to the missions by the Spanish government. The missions subsequently shuttered and fell into decay. To encourage settlement of the region the government issued grants of the mission lands to well-connected Californios; a total of 270 by 1846, including 33 in San Diego county. Note that the population of Alta California was so small in 1821 that it was not recognized as one of the constituent states of Mexico, but only as a 'territory.'

| Mexican Land Grants

While the Spanish made grants of land before the the Mexican Revolution, none were made in San Diego County. These grants, about 30 in all, were made for the life of the recipient, the crown retaining the title. The Mexican land grants were usually of two square leagues in area (14 square miles), or 8,856 acres. Note: a league was a unit of measure and was considered to be the distance a man could walk in an hour. These were permanent grants with full property ownership and inheritance rights. Grants included most of the California coast, San Francisco bay, along the Sacramento river and within the San Joaqin valley. Several requirements were laid on the grantee. The grant had to be surveyed and its boundaries marked, but since there were few surveyors in the region this rarely happened; the grantee could not subdivide or rent out the land; and public roads through the property could not be closed. In addition, some kind of residence had to be built on the land within a year of the grant. Most of the grants were ranchos dedicated to raising cattle. The owners styled themselves landed gentry, patterned on the Grandees of Old Spain. Workers on the ranchos were mainly natives, many former Mission residents. The cattle business in Alta California was principally for the hides which could be sold to shoe factories in New England. See Richard Dana's "Two Years Before the Mast" for an account and a glimpse of 1840's San Diego. |

On 15 June 1823 Mexican Governor Luis Antonio Arguello made the first land grant in San Diego county to Capitan Francisco Maria Ruiz. Ruiz was given a square league of land, or 4,400 acres, in Penasquitos (Little Cliffs) canyon. It included the eastern end of the canyon and mesas to the north and south that are now the suburbs of Rancho Penasquitos and Mira Mesa. The Mission padres wrote a letter to the governor stating that this land was theirs, used by the mission for sheep grazing, vineyards, and orchards, but their objections were ignored. Capitan Ruiz was the commandant of the San Diego Presidio and was given the land in lieu of a pension. His rancho became known as the Rancho Santa Maria De Los Penasquitos.

| Capitan Francisco Maria Ruiz

Francisco Ruiz, the son of Juan Maria Ruiz and Ana Isabel Carrillo, was born 1754 in Loreto, Baja California. He enlisted in the army when he was 26 and was sent to Alta California. He was promoted from sergeant to lieutenant in 1805 in Santa Barbara and then transferred to San Diego. Lieutenant Ruiz was Acting Commandant of the Presidio of San Diego from 1806 to 1807, relieving Lieutenant Manuel Rodriguez, and 1809 to 1820, relieving Captain Jose Raimundo Carrillo. Ruiz then became Captain and Commandant from September 1821 to 1827, when he retired at the age of 73. The Presidio had been relinquished by the Spanish on 20 April 1822. In 1824, or possibly earlier, Ruiz built the first house and planted the first orchard outside the presidio walls at Old Town. He kept this home and only occasionally visited his rancho. His house does not survive, but was located next to what today is the Pro Shop at the Presidio Hills golf course. Ruiz never married and died in 1839. |

In 1830 the settlement of San Diego, our "Old Town," consisted of about thirty houses located some three miles inland from the harbor, below the hill where the presidio was situated. The community’s 400-500 residents were mostly retired soldiers and their families. Those living in town cultivated small gardens and grazed their cattle on communal lands. In 1834, after receiving a petition from 432 residents for a civilian government, the Mexico City government recognized San Diego as a pueblo and granted it the right to municipal government and its own mayor, or alcalde. Three native pueblos were also established at this time, San Dieguito, Las Flores and San Pasqual. Only the latter survived for any length of time.

In 1834 Ruiz petitioned for and received another square league of land at the western end of the Penasquitos valley.

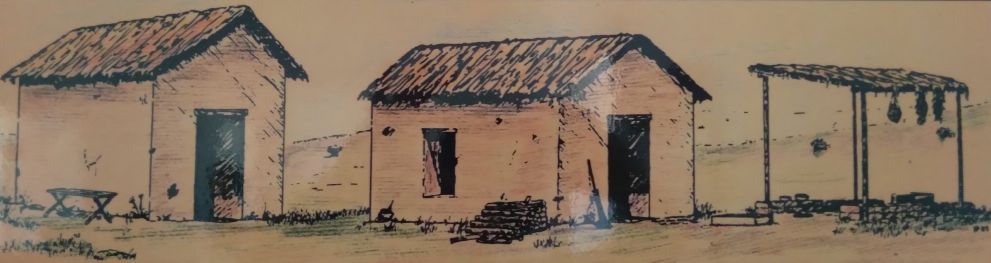

The Penasquitos adobe, shown as the Johnson-Taylor adobe in the map above, was orignally a pair of single-room thatch-roofed buildings with an open-air ramada, a brush structure enclosed by low adobe walls, to the east that served as a kitchen. It is the second oldest surviving residence in the county (the oldest is the Carrillo House in Old Town).

| Casa de Carrillo

Presidio Comandante Francisco Maria Ruiz built this house in Old Town in 1821 for his close relative and fellow soldier, Joaquin Carrillo, and his large family; 12 of his children lived to adulthood. It was located next to his 1808 pear garden lake. From this adobe dwelling, in April 1829, daughter Josefa Carrillo eloped to Chile with Henry Delano Fitch. When Ruiz died in 1839 and Joaquin soon afterwards, son Ramon Carrillo sold this property to Lorenzo Soto. It was transferred several times before 1932, deteriorating gradually, until George Marston and associates restored the house and grounds and deeded them to the City of San Diego as a golf course (Presidio Hills). The adobe is today the course's Pro Shop.  |

The old Ruiz adobe is today contained within the walls of the later Johnson-Taylor adobe. This first adobe was probably built in 1823 or 1824 as a center of operations for the overseer of the rancho. It has been suggested that the adobe may be older, being built for the overseer of the mission's herds, though this cannot be proven.

The adobe is well sited. The road from San Diego to San Pasqual, and on to Yuma, lay along the canyon and passed just north of the adobe.

"Beyond being a home, the ranch was also a way station on the wagon road to Warner's Ranch from San Diego via San Pasqual and Santa Ysabel Asistencia, from the 1840s. From 1857 to 1860 the rancho was a way station on that road for the coaches of the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line on the 125 mile route between San Diego and Carrizo Creek Station. Passengers were given meals here, served by the lady of the house."- from hiddensandiego.netTo the south of the site is Penasquitos creek and three perpetual artisian springs whose water flows in, underground, from far to the north. Penasquitos creek is, however, a seasonal river and the canyon was, at the time, much drier than today, supplemented as it is now by urban run-off. Most of the land was scrub with few trees; there was very little lumber available for building. In later years extensive cattle grazing further denuded the landscape

| Early Roads in Southern California

The El Camino Real was the earliest road in Alta California. It ran up the coast, connecting the 21 Spanish missions, along with a number of sub-missions, four presidios, and three pueblos. Interstate 5 covers much of this route today. The road to Yuma branched off the El Camino Real at what is today the 5/805 merge, progressing northeast, using several inland valleys, including Los Penasquitos, San Pasqual, and San Felipe, to avoid steep terrain and provide for adequate water stops. The trail passed out of the San Felipe valley, dropping into the desert where it then turned south to hug the mountains before turning east for Yuma. There were stops at Rancho Pensasquitos, San Pasqual village, Rancho Santa Ysabel, Warner's Ranch, Rancho San Felipe, Vallecito and Carrizo creek. |

The earliest foundation of the adobe so far located by archaelogists, dating from the 1820s-1830s, consists of 2 rows of large cobbles extending all the way across the approximate center of Wing A. The area between the 2 rows is filled with rubble and soil. A foundation of this size supported an exterior wall; when this wall was later knocked down, the adobe blocks at the corner were sheared off, and an eastern extension wall was built abutting the original wall. This second foundation was the base for Johnson's 1862 expansion of the earliest building. Three walls of wing A date to the Ruiz rancho.

Adobe is an unfired mudbrick made from soil, clay, water and straw. This mixture is placed in a form and air-dried until ready for use. The resulting product is not as strong as a kiln-fired brick and must be protected against moisture.

The floor of the Ruiz adobe was packed dirt. Such dirt floors in rural Mexico are maintained by a daily sweeping, augmented by a scattering of water to settle the dust. Eventually a hard surface results, similar to a heavily used dirt road.

The El Cuervo adobe, the ruins of which are at the western end of the valley, was built at least ten years after Ruiz' original adobe, when Ruiz was granted the western extension of his grant. This structure may have been intended as a bunkhouse for the vaqueros or a residence for the ranch foreman. It was presumably the home of Diego Alvarado when he owned the western end of the rancho. See Alvarado House for a c1900 view of this adobe.

The Rancheros, like Ruiz, acquired the large cattle herds that had once belonged to the Missions. These herds allowed the Californios to carry on business with trading ships visiting the coast. In exchange for hides and tallow, Californios received manufactured goods and other luxury items. Along with the former mission lands and herds. Californios also inherited the labor force of the missions. After the secularization of the Missions in 1833 Christian Indians were relegated to positions of servitude by the Californios. Christian Indians believed that the property of the missions belonged to them, and resented the Californios receiving any of it.

The Kumeyaay revolted and throughout 1836 and 1837 Indian attacks reached new heights, forcing the evacuation of ranchos and several times threatening San Diego itself. The population of San Diego dropped to just 150 in 1838 when the town lost its pueblo status and its mayor. It was subsequently administered by a Juez de Paz, or Justice of the Peace, as a sub-prefecture of the pueblo de Los Angeles. Rancho Penasquitos itself was attacked in 1837. Indian violence continued through 1842, which included a Kumeyaay siege of the town.

On 15 March 1837, Ruiz, who never married, appeared before the alcalde of San Diego, Jose Antonio Estudillo, and, "making known his advanced age," transferred the ownership of Los Penasquitos Rancho to his great nephew, Francisco Maria Alvarado, "in compensation for the board and care he had given him in times of failing strength and sickness." Francisco Alvarado's wife was Tomasa Pico, the sister of Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor of Alta California. Ruiz died in 1839. While Ruiz probably lived in Old Town most of his life, he must have occasionaly visited the rancho. In the year he died it was stated that,

"Captain Ruiz came back to the pueblo from his ranch in Los Penasquitos and died in the Carrillo home."

The Alvarados moved to the rancho, though keeping their house in Old Town. It is located just north of the Johnson House on La Plaza de las Armas.

| The Alvarado House

During the American period, the Alvarados increasingly spent time at Rancho Los Penasquitos, preferring to divide and rent out their valuable plaza properties to American businessmen. In 1854, Francisco Alvarado was charged with "keeping a disorderly house" because he got caught selling liquor. The little adobe building behind Alvarado House is known as the Alvarado Saloon. After 1874, the adobe slowly deteriorated. The reconstructed building, shown on the right, is a concession for Old Town State Park. |

Alvarado was active in political affairs in San Diego. In 1837 he was first regidor, or alderman, he was treasurer in 1840 and 1841, justice of the peace in 1845, and an elector in 1850. However, the ownership of the Penasquitos rancho did not make the Alvarados rich. Alfred Robinson revisited San Diego in 1840 and observed that,

"everything was prostrated, the Presidio ruined, the Mission depopulated, the town almost deserted, and its few inhabitants miserably poor."The Californios of the San Diego county region, while they assumed the air of Grandees, were rich only in land, having only a limited cash income before the time of the American occupation, which started in 1846, and they did not prosper in the 1850s.

The population of Alta California were not happy with the rule from Mexico City, unsuccessfully rebelling in 1831, 1836 and again in 1845. Their resentment was based on the imposition of Governors appointed by Mexico City who had little knowledge of local conditions and with laws passed without consideration of the Californios' concerns.

The Mexican-American War broke out in 1846 over the admission of Texas, considered to be a province in revolt by Mexico, into the United States. In 1846, the American Army of the West, commanded by General Stephen Kearny, stopped at the Penasquitos adobe on their way to San Diego to get water and seize provisions after their defeat at the Battle of San Pasqual. Lieutenant W. H. Emory recalled that when the United States military force he was with arrived at the Penasquitos Rancho, they seized all the property they did not destroy because the owner opposed the Americans.

| The Battle of San Pasqual

On 6 and 7 December 1846, General Stephen W. Kearny's US Army of the West, along with a small detachment of the California Battalion led by a Marine Lieutenant, engaged a small contingent of Californios and their Presidial Lancers Los Galgos, the Greyhounds, led by Major Andres Pico. A series of engagements occurred down the San Diegquito river, then known as the San Bernardo, culminating in U.S. forces atop Mule Hill, surrounded by the Californios. After U.S. Navy and Marine Corps reinforcements from the USS CYANE arrived from San Diego, the Californios were forced from the field and Kearny's troops were able to reach San Diego. Who won the Battle of San Pasqual? The Americans suffered the most casualties, but they held the field at the end of the day. See also, CA Parks and Recreation: The Battle of San Pasqual. |

After the war the Californios, not surprisingly, experienced a decline in economic status, political power and social influence. Located too far to the south, San Diego ranchos were unable to benefit from the increase in cattle prices caused by the influx of gold-miners in 1849. The weather also turned dry and hot during the 1850s resulting in great hardships for county residents. The rancho economy of San Diego declined throughout the period.

In the 1850 census there were less than 1,000 non-native inhabitants in San Diego county.

Maria Estefana Alvarado, a daughter of Francisco Alvarado and a reputed 'beauty,' married George Alonzo Johnson on 4 June 1859. A 49er, George ran the Yuma ferry and a riverboat company that serviced the US Army at Fort Yuma, in Arizona, earning the courtesy title of Captain. As the only steamboat company on the river, Johnson and his partners became wealthy after the discovery of gold along the Colorado River in 1858. In 1858 he had moved to San Diego where he met and subsequently married Estefana. Johnson built a fine home in Yuma for his new wife, but Maria did not like Yuma and convinced her husband to return to San Diego.

| George Alonzo Johnson

Seeing the opportunity in bringing supplies to the isolated post of Fort Yuma, in 1852 Johnson and his partner Benjamin M. Hartshorne contracted to carry supplies up the Colorado in poled barges. This failed due to the strong current and many sandbars in the river. After a steam tug, the 20 hp Uncle Sam, was successfully used to ascend the river in 1853, Johnson formed George A. Johnson & Company with Hartshorne and another partner, Captain Alfred H. Wilcox. They brought the disassembled side-wheel steamboat General Jesup to the Colorado River Delta. There in the estuary he assembled this more powerful 70 hp steamboat and began successfully shipping cargo and carrying passengers on the Colorado River from its mouth, up to Fort Yuma. His steamboat carried 50 tons of cargo to the fort in 5 days and brought the cost to supply the fort down to $75 a ton from the $500 a ton shipped across the desert from San Diego. It made the Company $4,000 per trip to ships in the mouth of the Colorado River. Johnson was instrumental in getting Congressional funding for a military expedition to explore the Colorado River above Fort Yuma in 1856. Cut out of providing the steamboat for the 1857 expedition of Lt. Ives, Johnson at his own expense took the General Jesup up river first exploring the river up to what is now Nevada. As the only steamboat company on the river, Johnson and his partners became wealthy after the discovery of gold along the Colorado River in 1858. In 1858 he moved to San Diego, where he married a famous beauty, Maria Estefana Alvarado on 4 June 1859, in San Diego, California. Her parents gave Johnson's wife the Rancho Santa Maria de Los Penasquitos as a wedding present. Johnson also built a home in Yuma for his wife for when they traveled there, that became the commanding officers quarters of the Yuma Quartermaster Depot in 1864. The Johnsons had nine children, but only two lived to adulthood. In 1863, Johnson became a Member of the California State Assembly for the 1st District, and again in 1866–67. Johnson had delegated operations to his senior steamboat captain, Issac Polhamus, and distracted by his rancho and political career did not invest in more shipping to keep up with the growing traffic caused by the 1862 Colorado River gold rush. By 1864 it had created a large backlog of undelivered freight and caused competition of opposition lines to arrive on the Colorado River. This finally forced Johnson to expand his fleet of steamboats and to begin to use barges to increase their cargo carrying capacity. Following a price war that lasted until 1866, with the advantage of the contracts to supply the U. S. Army posts and his system of wood-yards, Johnson's company was again the only steamboat company on the river. In 1869 he incorporated his steamboat company as the Colorado Steam Navigation Company which he and his partners held until they sold its steamboats to the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1877. Johnson acquired title to the Rancho Los Penasquitos when the U.S. government granted a patent to the land in 1876. In 1880, the Johnsons lost their rancho to creditors and within several years moved to a building, now known as the Johnson House, which they owned on the plaza of San Diego where they remained until his death. He died in 1903 at the age of 79 and was buried in San Diego. |

Upon the death of Francisco Alvarado, his son, Diego, inherited the rancho. After his marriage, George Johnson bought the eastern half of the rancho from him and, in 1862, Diego sold his remaining half to his sister and Johnson.

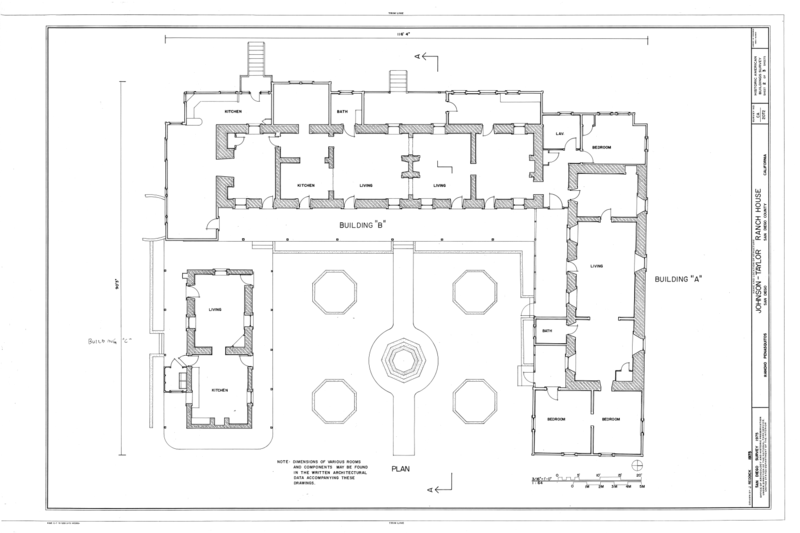

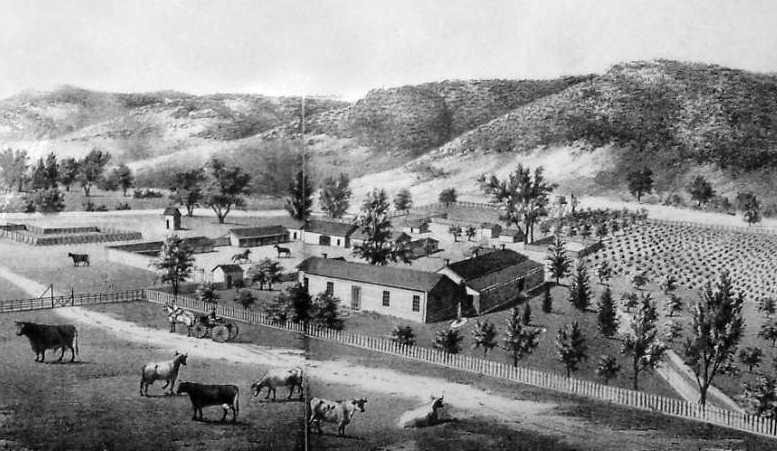

George Johnson set about expanding the modest ranch house, spending $30,000 on the work. A ramada kitchen, to the east of the adobe, was enclosed and added to enlarge the old adobe. Two new wings were added to the house, known today as wings B and C. The latter contained the kitchen.

The following is a description of the rancho by a (very flowery) journalist,

"At the request of Captain George A. Johnson, in company with some friends, we paid a visit last week to Penasquitos, the Captain’s home. The ranch is situated about 16 miles from San Diego and some four or five miles from where the road to Los Angeles passed through the Soledad Valley. The road was in fine condition and the ride was exceedingly exhilarating. Among those lovely valleys, it passed, crossing, sometimes, gurgling streams of water, shaded by large trees filled with birds of silvery voices and among flowers of the most beautiful hues. We were but a little more than two hours in making the trip. No pen can describe the beauties of the scene by which the house is surrounded, situated in a valley near a little stream skirtedby tall and graceful cottonwood and slender willows; on either hand, the hills roll back in graceful undulations covered with verdure and flowers of every color. The lands around the house are tastefully laid out and filled with fruit and ornamental trees, grape vines, strawberries and vegetables. The Captain has displayed a great deal of taste in his election of trees and shrubbery and a disregard for expenses in preparing his grounds. A little below the house he has built a tank, or reservoir, 65 feet long by 35 feet in width and about 3-1/2 feet in depth. The sides are built of stone with a cement hard as flint. Into the reservoir, a stream of water supplied by a large spring is constantly flowing and upon the water-clear as crystal-ducks of several fine varieties are always swimming. The Captain’s residence is not only commodious, but most conveniently planned and tastefully furnished; while the outhouses, barns, stables, milk house, wash house and bath house are in keeping with the dwelling and are well adapted to the convenience and pleasure of a gentlemen of taste and refinement. He has a couple of fine stallions, the pride of his eye, and some of the finest colts in the country. He is a prince in generosity and knows, not only how to live and take comfort, but how to make others comfortable and happy around him. With such a host in such a place and more than all-beneath the benign influence of amiable and accomplished horses, how else could the hours pass except more pleasantly." - from the "San Diego Union" of 28 April 1869

Johnson explored the development of the many springs on the property. In 1869 he was named as a trustee for the newly-formed San Diego Water Company - from the "Sacramento Daily Union" of 24 March 1869. He promoted the high volume of water from his springs through water surveys, which claimed that there was enough water to supply a city of 100,000 - from the "San Diego Union Weekly" of 4 April 1871. There was continuing discussion of using the Penasquitos watershed to supply the city or a new community; dams and reservoirs could be built by taking advantage of natural basins - from "The Daily World" of 25 September 1873.

George built a reservoir, or "tank," between the adobe ranch house and the creek; a spring flowed into the reservoir, and then into the garden from the overflow - from the "San Diego Union Weekly" of 28 April 1869 & 4 April 1871. Johnson also built a spring house around the spring nearest the reservoir - from "The Daily World" of 24 September 1873. However, every few years the springs would mysteriously dry up. On some occasions this was due to earthquakes, which were mentioned as the cause of irregular water flow.

The Johnsons lost their rancho to creditors in 1880 through a combination of taxes, a country-wide Depression, and $90,000 owed him by the government that could not be paid. Within several years the Johnsons moved to a building, now known as the Johnson House, which they owned in Old Town where they remained until George's death in 1903. He was buried in the Mount Hope cemetery. Maria Estefana died in 1926 in Glendale, California.

The rancho went through several hands before being sold to Jacob Shell Taylor. Taylor, a successful rancher from New Mexico, remodeled the ranch house and promoted it as a hotel, as well as stagecoach stop on the San Diego to Yuma road. It was probably at this time that the kitchen, Wing C, was enlarged into a 30' square Victorian-style kitchen and dining room. At the same time Taylor was also developing Del Mar as a destination resort.

| Jacob Shell Taylor

Colonel Jacob Shell Taylor was a rancher and developer who established the town of Del Mar, bought the Rancho Pensasquitos, and owned the Stonewall gold mine near Julian. Hearing that the railroad was extending southward from Los Angeles, he had a depot built on the coast and, in 1885, bought 338 acres nearby to create his new town. A year later, Taylor opened the Casa Del Mar, "House of the Sea," steps away from his depot, on the edge of the bluff between 10th and 11th streets. Unfortunately, heavy rains in 1888 washed out the train tracks, some houses in Del Mar and the foreseeable future for Del Mar tourism. The economic crash of the late 1880s further damaged Taylor's position. Finally, the Casa Del Mar burned to the ground in 1889. He collected the insurance money and split for Texas. |

Taylor planned to subdivide the rancho, selling 10-acre lots for $250 (see the numerous advertisements for the sale of property in the 'Los Penasquitos Colony' in the San Diego Union). However, a recession in the 1880s resulted in him losing the property.

Taylor planned to subdivide the rancho, selling 10-acre lots for $250 (see the numerous advertisements for the sale of property in the 'Los Penasquitos Colony' in the San Diego Union). However, a recession in the 1880s resulted in him losing the property.

Adolph Levi, a speculator, bought the rancho and, then later, sold it, in 1910, to Charles F. Mohnike. Mohnike lived in Chula Vista where he already had large orchards. His family lived at Los Penasquitos only for the summers, using the house as a retreat. The Mohnike barn was built around 1910. Mohnike raised sheep, horses, and Hereford cattle on the rancho and introduced new agricultural technologies through the implementation of a combine harvester that was pulled by twenty horses to cut and bail wheat.

In 1912 Wing C of the ranch house, the Victorian kitchen/dining room, burned in a fire started by drunken cooks, according to Evangeline Mohnike in an oral history she provided. The fire was so hot that a cast-iron stove melted. The adjacent end of Wing B was also damaged. This event terrorized Mohnike's wife as it had taken a long time to locate and ensure the safety of their children. Mohnike decided to move the family out and he built the third adobe in the valley east of what is now the Equestrian Center on Black Mountain road. Mohnike rebuilt the kitchen and other damaged areas of the ranch house, which was then used as a bunk house. In 1913 a killing frost hit San Diego, killing the majority of Mohnike's fruit trees.

George Sawday and Oliver Sexon bought the property in 1921 and turned it into one of the largest cattle ranches in Southern California. The house continued to be used as quarters for the cowhands and their families. A modern kitchen and bathrooms were added around 1940.

In 1974, the County of San Diego acquired land around the adobe ranch House in a community effort to develop Los Pennasquitos Canyon Preserve.