|

The Battle of San Pasqual |

|

|

The Battle of San Pasqual |

|

| Links: The Mexican War and California | San Diego Reader Stories | Marine Corps Study Package | The Battle | |

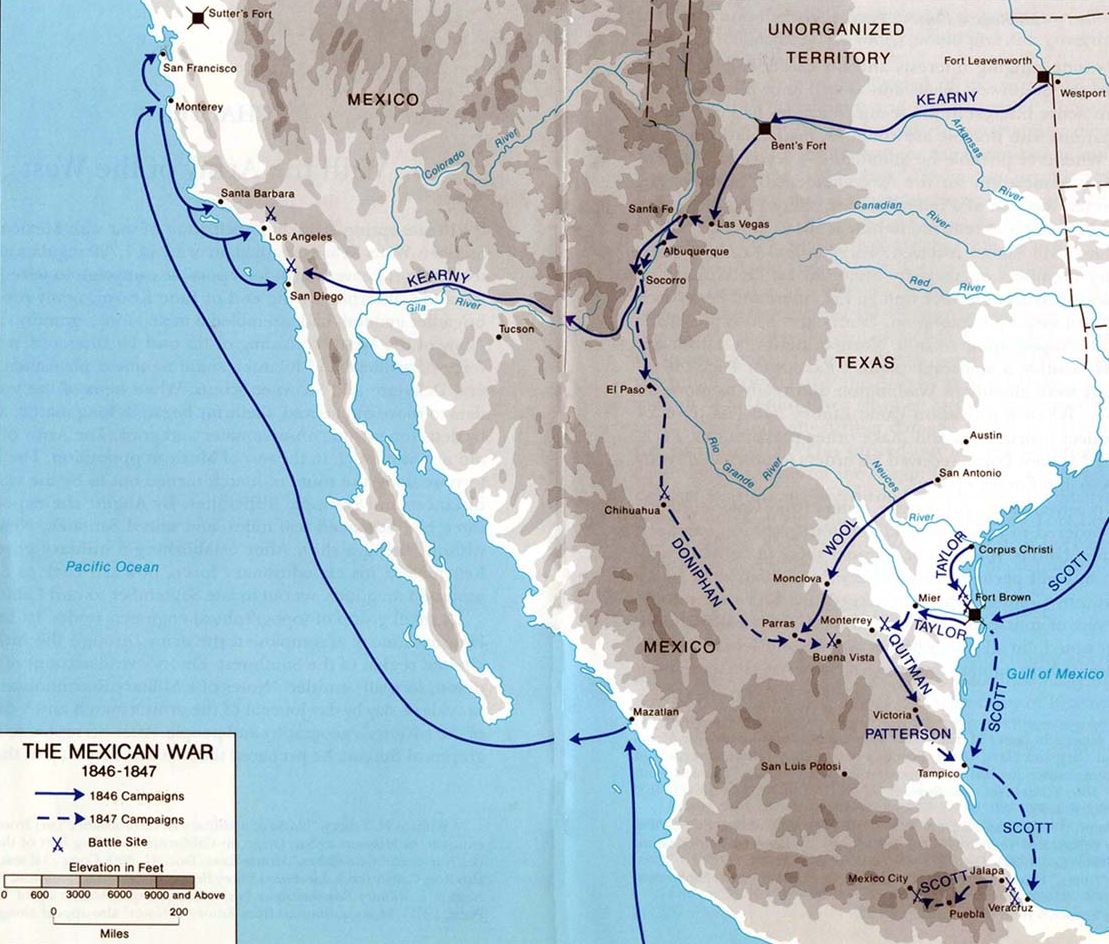

The Mexican-American War began as a dispute over the territory of Texas. Previously a province of Mexico, Texas had revolted in 1836 and, after the Battle of San Jacinto, had gained its independance. Mexico disputed this and considered Texas, while in revolt, to still be a part of the Mexican state. In 1845 Texas requested admission into the United States of America. This was granted early in 1846 and American military forces moved into the disputed territory. This resulted in a battle with Mexican forces that cost a number of American lives. In consequence, on 13 May 1846 Congress declared war on Mexico.

General Stephen Kearny, the commander at Fort Leavenworth in what would later become the state of Kansas, was given the task of securing the territories of New Mexico and California, establishing civilian government within the seized territories, and to "act in such a manner as best to conciliate the inhabitants, and render them friendly to the United States." His "Army of the West" consisted of the 300 regular Army men of the 1st Dragoons, a cavalry unit, 850 men of the Missouri Mounted Volunteers under their elected leader, Alexander Doniphan, 100 cavalry of the LaClede Rangers, 100 volunteer infantry, 150 men of a Missouri volunteer artillery battalion and 50 Shawnee and Delaware scouts. The 500 man Mormon Battalion, raised in Iowa, followed Kearney's force, but never caught up with them.

The Army of the West left Fort Leavenworth in June 1846. With them they brought 1,556 supply wagons and approximately 20,000 cattle and other stock to feed the troops on their long march.

Kearney led his force southwest towards the Sante Fe trail, which ran along the Arkansas river, across Kansas and Colorado. The trail then turned south, at Bent's Fort, and across the narrow, treacherous Raton Mountain Pass to Sante Fe.

While the American's were informed by locals on several occasions that large Mexican forces were 'just a days march ahead' ready to oppose them, on each occasion they found only fortifications recently abandoned. Kearney entered the New Mexico territory's capital of Santa Fe peacefully on 18 August. After organizing a new civilian government Kearny left for California with 300 of his Dragoons, leaving the majority of his army to occupy New Mexico. Kearny ordered Colonel Doniphan to take a portion of his Mounted volunteers, about 800 men, into the Mexican State of Chihuahua to occupy it as well.

Out of Sante Fe, Kearney led his diminished force along the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, or Royal Road of the Interior Land, south along the Rio Grande river.

The decision to take just 300 men on the march west was based on the difficult logistics of crossing the Arizona desert. A larger force would not have been able to find sufficient fodder for their animals or water for their men. Of these 300, Kearny later sent back 200 after meeting with American scout Kit Carson south of Socorro on 6 October. There he had learned of the peaceful seizure of California by the U.S. Navy, under the command of Commodore Robert Stockton. Convinced the war was over, Kearny sent most of his dragoons back to Santa Fe, keeping only Companies C & K, about 100 men, as well as his two 12 pound mountain howitzers, see photograph to the right. Also convinced that traveling with wagons would slow him down, the General returned those too, using instead pack mules to carry his supplies. Kearny commandeered Kit Carson to act as a guide.

The decision to take just 300 men on the march west was based on the difficult logistics of crossing the Arizona desert. A larger force would not have been able to find sufficient fodder for their animals or water for their men. Of these 300, Kearny later sent back 200 after meeting with American scout Kit Carson south of Socorro on 6 October. There he had learned of the peaceful seizure of California by the U.S. Navy, under the command of Commodore Robert Stockton. Convinced the war was over, Kearny sent most of his dragoons back to Santa Fe, keeping only Companies C & K, about 100 men, as well as his two 12 pound mountain howitzers, see photograph to the right. Also convinced that traveling with wagons would slow him down, the General returned those too, using instead pack mules to carry his supplies. Kearny commandeered Kit Carson to act as a guide.

| The U.S. Navy in San Diego

In 1842 the Pacific Squadron commander received false information that war had begun between the United States and Mexico. In response they occupied the town of Monterey, the terriotorial capital. They quickly returned the town when they discovered their error. In 1846 the Pacific Squadron consisted of ten ships: two ships of the line, COLUMBUS & OHIO (neither of which saw action); two frigates, CONGRESS & SAVANNAH; two sloops-of-war, WARREN & DALE; and four sloops, CYANE, PORTSMOUTH, LEVANT & ERIE. In May 1846, after a declaration of war, the frigate USS SAVANNAH, and sloops USS CYANE and USS LEVANT of the Pacific Squadron again took Monterey. Early in July the USS PORTSMOUTH took Yerba Buena, today's San Francisco.

In early August USS CONGRESS took Santa Barbara. After a week in San Diego Fremont set out overland with about 120 men to assist Commodore Stockton in his capture of Los Angeles, leaving behind a garrison of about 40 men. CYANE's detachment returned aboard to sail south to San Blas. Los Angeles was taken on 13 August. Mexican General Jose Castro and Governor Pío Pico, opponents in the rule of Alta California, had fled the Pueblo of Los Angeles before the arrival of American forces. On 27 September the Californios in Los Angeles revolted against the Americans and succeeded in recapturing the pueblo on 4 October. Then Francisco Rico and Serbulo Varela were sent with fifty men to recapture San Diego. Captain Ezekiel Merritt and John Bidwell, who were in charge of the American garrison in San Diego, feared that they would be overrun and so the Americans and a few of their Californio supporters decided to abandon the town. The Californios went to their ranchos, the Americans and a few allies boarded the whaling ship STONINGTON anchored in the harbor. Without firing a shot the Mexicans recaptured San Diego from the Americans in early October. The Mexican partisans held on to San Diego for three weeks until 24 October when an American soldier sneaked ashore and spiked the Mexican cannons on the hill where the old presidio had been. Then American volunteers attacked. After a brief skirmish the Americans took possession of the town and hauled down the Mexican flag. Two days later a force of 100 Californios laid siege to the Americans and their sympathizers in San Diego. On 1 November Admiral Stockton arrived with reinforcements. The Americans sent out Indian scouts to assess the Californio strength and received reports that there were about fifty of them located at Rancho San Bernardo, 20 miles north of San Diego, but that many more surrounded the pueblo of San Diego. During the siege the Americans built an earthen fort on top of Presidio Hill. On 1 December the Americans at the San Diego pueblo learned that General Stephen Kearney’s dragoons were about eighty miles away at Warner’s Pass. Commodore Stockton ordered an escort of 27 mounted riflemen, commanded by Captain Archibald Gillespie, USMC, to march north to meet them. This force was joined by Lieutenant Beale and Midshipman Duncan, U.S. Navy, 10 Navy Carbineers and one artillery piece (the Sutter gun). They met General Kearney at Rancho Santa Maria, today's Ramona, just before the Battle of San Pasqual. |

With the aid of Kit Carson, the Army of the West found a route through the Black Range mountains to the Gila river. They followed that river through the Arizona desert to the Colorado, at what today is Yuma, then across today's Imperial valley to the Cuyamaca mountains, east of San Diego. They climbed these slantwise to the northwest, finally coming to Rancho San Jose del Valle, commonly known as Warner's Ranch for its owner, John Warner. This was a ranch set in a high, cool mountain meadow.

Kearny's force reached Warner's Ranch in California on 2 December. The arduous march through the Arizona desert had reduced men and beasts to starvation. The force was travel weary, their uniforms in tatters and their boots falling apart. Many horses had been lost and the rest were unfit for further service. They desperately needed to replace these exhausted mounts, but were only able to obtain half-broken mules and horses from the local area.

While his men rested, General Kearny sent an advance party ahead to advise Commodore Stockton, then in San Diego, that he had annexed the New Mexico territory and was now in California, and requested some well-mounted volunteers be sent forward to guide his force.

They then continued their march, advancing past the Mission Santa Ysabel to the Rancho Santa Maria (also known as Rancho Valle de Pamo), on the plateau where the town of Ramona now stands. Here, on a wet 5 December, they made camp.

Admiral Stockton had received word from Kearny's advance party and, on 3 December, ordered an escort of 27 mounted riflemen, commanded by Captain Archibald Gillespie, U.S. Marine Corps, to march north to meet him. This force was joined by Lieutenant Beale and Midshipman Duncan, U.S. Navy, 10 Carbineers and one artillery piece, a Russian made four-pounder, the so-called Sutter Gun. See The Saga of the Sutter Gun for more about this weapon. Rafael Machado, a Californio from San Diego, was the unit's guide. Lieutenant Gillespie's force intercepted Kearney just north of Rancho Santa Maria where Gillespie informed Kearney about the state of the country ahead and warned him that a band of 'insurgents' led by Don Andres Pico was reported to be no more than six miles away at the Kumeyaay pueblo of San Pasqual.

Andres Pico, the younger brother of Mexican Governor Pio Pico, had gathered a contingent of about 100 Californio ranchers and landowners to retake San Diego, which was then under the control of the U.S. Navy. The Californios were lancers, mounted on horseback and carrying long lances as their primary weapon. They were proud of their excellent horsemanship.

"They were mounted on elegant horses, and are without exception the best horseman in the world." - from Lt. Watson, USMC, describing the Mexican cavalry before the battle outside Los AngelesAmong the men were Juan and Jose Alvarado, brothers-in-law of Joseph Snooks, the owner of the Rancho San Bernardo. Don Leonardo Osuna of the Rancho San Dieguito, now Rancho Santa Fe, was also there.

Pico, alerted that there was an American army headed west, commandeered the native village of San Pasqual, at the eastern end of the valley, taking possession of the natives' huts and slaughtering a number of their cattle to feed his troops.

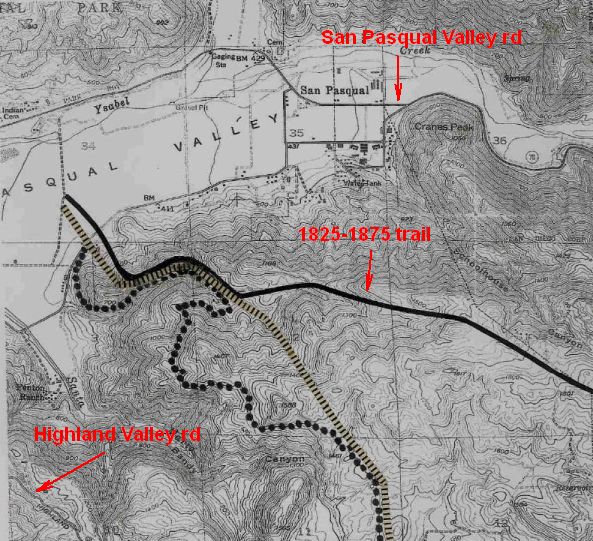

Kearny, eager to engage the Californios, sent scouts forward, down a narrow trail [see the 1825-1875 trail, below] into the valley, to reconnoiter the enemy's position.

However, the scouts were, in turn, spotted by Pico's men. The Californios subsequently prepared for battle. Knowing he had lost the element of surprise, Kearney ordered an immediate attack in early morning of 6 December. Unfortunately, a heavy rain that night not only dampened the morale of the dragoons, it dampened the powder used in their carbines making most of the guns useless, except as clubs. This left the soldiers with their cavalry sabers as their main weapon.

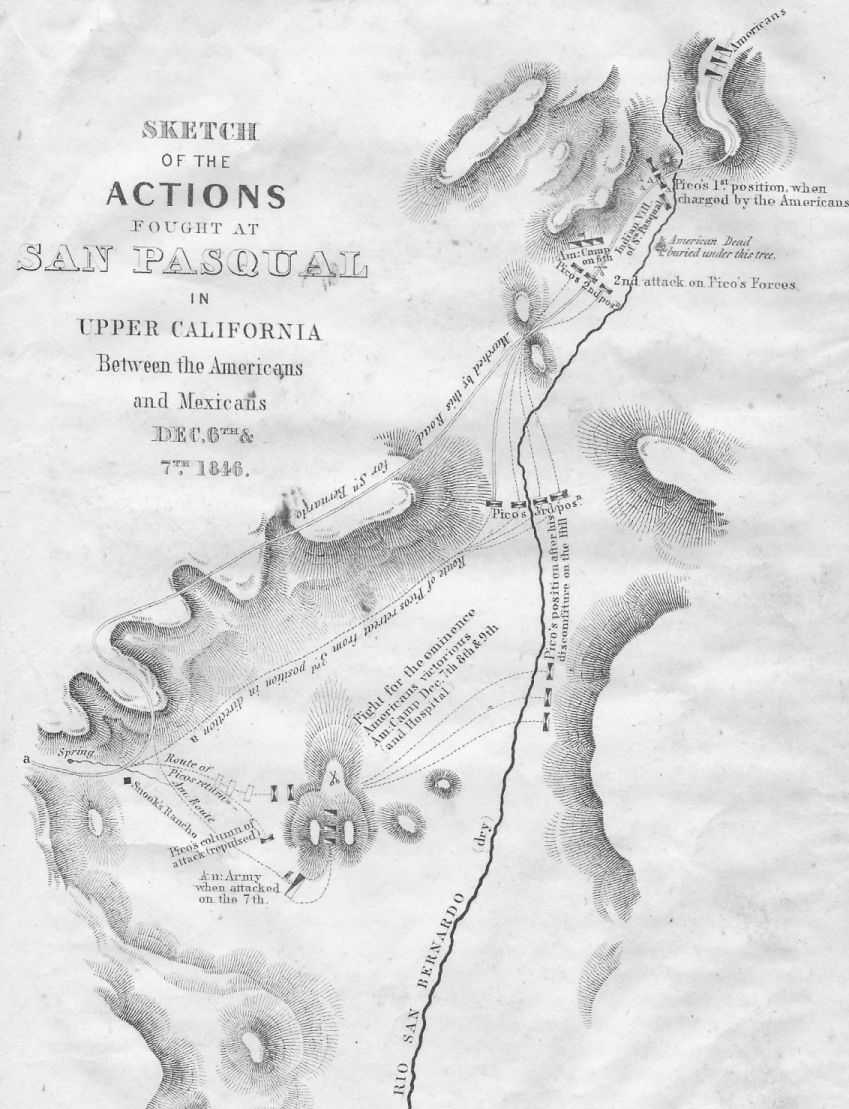

*The map below was made by Lieutenant Emory, a member of General Kearney's command. Emory was an Army topographic surveyor. The map is oriented with East at the top.

The American dragoons advanced out of the east in a column of twos, down from the ridge into the valley below with an advance guard of 12 dragoons mounted on the best horses available. A native woman of the San Pasqual recalled that,

"Early one rainy morning we saw soldiers that were not Mexicans come riding down the mountain side. They looked like ghosts coming through the mist and then the fighting began." - Felicita, daughter of Chief Panto

The American force became strung out and, as the order to "trot" in preparation for the final charge was made, the advance guard of 40 dragoons, under the command of Captain Johnston, misheard this as an order to "charge."

This forward element quickly became separated from the main group and, in the excitement, the mules pulling the two small mountain howitzers bolted.

The lancers made a tactical retreat, leading the forward element on and further seperating the Americans. The Californios then wheeled about and engaged the unsupported forward guard, lances at the ready.

The travel weary Americans and their untrained mounts, unprepared for the counter-attack and the Californios' long lances, sustained 21 dead, including Johnston, and 15 wounded.

However, when a four-pounder cannon (apparently loaded with canister shot) was finally brought into play the lancers withdrew. The Californios had 15 casualties during the engagement and just one dead.

Kearny gathered his forces and retreated to a knoll just northwest of the village of San Pasqual while Pico's men rode off down the valley. The Americans camped for the night on the knoll.

"When night closed in, the bodies of the dead were buried under a willow to the east of our camp, with no other accompaniment than the howling of myriads of wolves, attracted by the smell. Thus were put to rest together and forever, a band of brave and heroic men." - Lieutenant William H. Emory

The next day the Americans rode west, on the northern side of the valley, shadowed by the lancers. The Americans then turned south to continue towards San Diego. They came upon the adobe hacienda of Joseph Snooks, the owner of Rancho San Bernardo. Stopping there, they seized badly needed supplies. Snooks was absent, onboard his schooner bringing up supplies for the Californios.

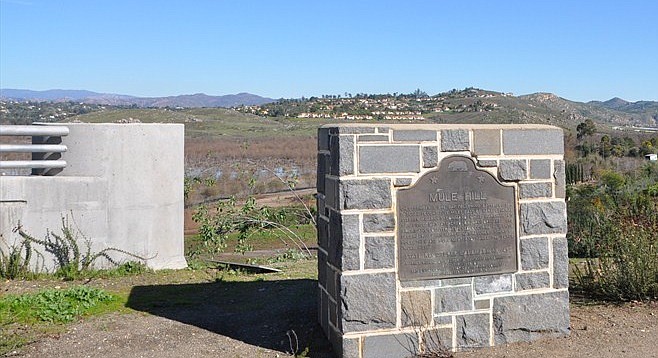

Continuing south as they left Snook's home, the Americans again ran into Pico's men. During the encounter a rush was made for the high ground of Mule Hill, which the Americans won. Pico then surronded the hill and began a siege.

On the hill Kearny's men settled down for a long stand-off. They slaughtered a mule for food, giving the hill its name [this mule may have already been shot by the Californios in the precious encounter]. Three men then volunteered to sneak through Pico's lines and get aid from Naval forces already in San Diego. These men were Lieutenant Edward Beale, the scout, Kit Carson, and a young native guide named Chemuctah, of the Luiseno people. Under cover of darkness they each took different routes to the Navy Commodore's headquarters in San Diego.

Meanwhile Andres Pico received orders from Governor Flores to abandon his siege of the Americans and return to Los Angeles to rescue him from an insurrection from within the Californio ranks.

| The Location of Mule Hill

In 1921 the California Historical Survey Commission determined that the Siege, or third engagement, of the Battle of San Pasqual had taken place at what became known as Battle Mountain. This is a large hill, south of the river, within the suburb of Rancho Bernardo. They made this determination despite acknowledging that this did not comport with the evidence of Lieutenant Emory's contemporary map of the engagement. "With the exception of the course of the San Bernardo (or San Dieguito) River, which is indicated by Emory as running east of the American camp of December 7-11 [actually it shows it to the south], the map mentioned is exceedingly accurate . . . The one serious defect in Emory's map is met in locating the latter part of the route [of Kearney's force towards the final engagement] just described, as he indicates the San Bernardo river as running to the east of the site of this third battle, when in reality it runs to the north of the peak [of Battle Mountain] . . ." - from "The Battle of San Pasqual" by Owen C. Coy, Ph.D., 1921The writers of the report cited, seemingly convinced of the rightness of their determination of the siege's location, deemed that Emory became confused about the location of the river because it was dry at the time and he didn't realize that the American force had crossed it. In 1970 an effort was made to identify the true location of Kearney's camp and of Mule Hill. "The evidence demonstrates that the site now designated as Mule Hill is not the correct hill, and that the large hill with the two prominent rock outcrops on its western end is the true Mule Hill. The evidence further shows that the Kearny Column camp was on the large hill in the area immediately to the east of the two big rock outcrops since three-quarters of the artifacts of the period were found in this area. The study of the Kearny Column march route places it along the dry road route described, and the route approaching from the north could have taken Kearny only to the large hill since he could not see the small hills from this aspect. The artifacts found on the large hill are the remains of the baggage which the Kearny Column burned on Mule Hill to prevent its falling into the hands of the Californians in the event they had to surrender. In addition, the large hill is the only one in the general Mule Hill area big enough to have afforded a readily defended campsite for the 125 men of the Kearny Column, their remaining animals, baggage, and two cannon. Finally, the latitude and longitude of the Mule Hill camp site, as recorded by Lieutenant Emory [117° 03′ 29″ west and 33° 03′ 42″ north], are further proof that this is the true Mule Hill." - from "A Study of the Location of Mule Hill" by Konrad K. Schreier, Jr.The true Mule Hill, below, is a small prominence north of the river, within the San Dieguito river park.   Mule Hill Historical Marker, facing Mule Hill across the San Dieguito river The Historical Marker reads, "On December 7, 1846, day following battle of San Pasqual, fought five miles east of here, General Stephen Kearny's command while marching on San Diego was attacked by Californians. The Americans counter-attacked, occupied hill until December 11 when march was restored. Short of food, they ate mule meat and named the place 'Mule Hill.'"Battle Mountain presumably earned its name by its proximity to the battlefield, though I've no where seen that recorded. A cross, placed on top of Battle Mountain by a religious group in 1966, was rededicated to the victims of the Tenerife air disaster in 1977. |

All three volunteers made it down to San Diego and the Californios retreated when 200 U.S. Navy and Marine reinforcements from San Diego arrived on 11 December. On the way back down to San Diego the American army passed the Rancho Penasquitos adobe and seized supplies there as they had at Snook's place.

Eventually U.S. forces were able to force the Californios to surrender and an armistice was signed on 13 January 1847. With the Americans reoccupying Los Angeles and San Diego the guerilla forces in the countryside disbanded. The war was officially over for the Californios.

See also the following excellent article from The Reader, The Bloody Battle of San Pasqual.

| Edward Fitzgerald Beale (1822-1893)

Beale later carried packages for Navy Secretary Bancroft to Stockton, sailing to Panama, crossing the isthmus by boat and mule, and then sailing to Peru to meet up with Stockton and the CONGRESS in 1846. He sailed with Stockton to Honolulu, and then to California. Hostilities with Mexico had already begun when the vessel reached Monterey, California. After reaching San Diego, California, Stockton dispatched Beale to serve with the land forces. Beale and a small body of men under Captain Archibald Gillespie joined General Stephen W. Kearny's column just before the Battle of San Pasqual on 6 December 1846. After the Mexican Army surrounded the small American force and threatened to destroy it, Beale and two other men crept through the Mexican lines and made their way to San Diego for reinforcements. Two months later, although Beale still suffered from the effects his adventure, Stockton again sent him east with dispatches. After leaving the Navy, Beale returned to California as a manager for William Henry Aspinwall and Commodore Robert F. Stockton, who had acquired large properties there. In 1853, President Fillmore appointed Beale Superintendent of Indian Affairs for California and Nevada. On his way to California, Beale left Washington on 6 May with a party of 13 and surveyed a route across Colorado and Utah to Los Angeles, California, for a transcontinental railroad. Beale served as Superintendent until 1856. California Governor John Bigler appointed Beale a brigadier general in the California state militia to give Beale additional authority to negotiate peace treaties between the Native Americans and the U.S. Army. In 1857, President James Buchanan appointed Beale to survey and build a 1,000-mile wagon road from Fort Defiance, Arizona to the Colorado River, on the border between Arizona and California. The survey also incorporated an experiment for the Army using camels, first proposed by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis four years earlier. Beale used camels from the Camel Corps imported from Tunis as pack animals during this expedition and on another in 1858 through 1859 to extend the road from Fort Smith, Arkansas to the Colorado River. His lead camel driver was Hi Jolly (Hadji Ali) a Greek-Syrian convert to Islam. The camels were capable of traveling for days without water, carried much heavier loads than mules, and could thrive on forage that mules wouldn't touch. But the camels scared horses and mules, and the Army declined to continue the experiment. Nevertheless, the wagon road Beale built became a popular immigrant trail during the 1860s and 1870s. At the urging of Beale, Fort Tejon was established by the U.S. Army in 1854 to protect and control the Indians who were living on the Sebastian Indian Reservation, and to protect both the Indians and white settlers from raids by the Paiutes, Chemehuevi, Mojave and other Indian groups of the desert regions to the east. Fort Tejon was abandoned in 1864. In 1865 and 1866, Beale purchased the Mexican land grants which now comprise the 270,000-acre Tejon Ranch. When the U.S. Army sold its camels, Beale purchased some of them and kept them at his ranch. Tejon Ranch is the largest private landholding in California, and today is owned by Tejon Ranch Company, a company listed on the New York Stock Exchange In 1871, Beale purchased Decatur House, opposite the White House, in Washington, D.C. Decatur House had been built in 1818 for naval hero Stephen Decatur. Beale's daughter-in-law, Marie, bequeathed Decatur House to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1956. President Grant appointed Beale Ambassador to Austria-Hungary, in 1876. He served from 1876 to 1877,[6] and displayed a talent for diplomacy. His lavish entertaining, tales of the American West, command of foreign languages, and warm personality made Beale and his wife popular figures in the Viennese court. - from Wikipedia |